A race is on in solar engineering to create almost impossibly-thin, flexible solar panels. Engineers imagine them used in mobile applications, from self-powered wearable devices and sensors to lightweight aircraft and electric vehicles. Against that backdrop, researchers at Stanford University have achieved record efficiencies in a promising group of photovoltaic materials.

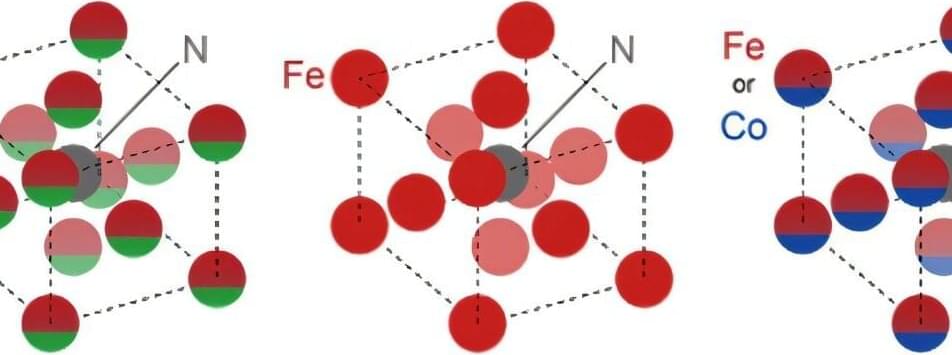

Chief among the benefits of these transition metal dichalcogenides – or TMDs – is that they absorb ultrahigh levels of the sunlight that strikes their surface compared to other solar materials.

“Imagine an autonomous drone that powers itself with a solar array atop its wing that is 15 times thinner than a piece of paper,” said Koosha Nassiri Nazif, a doctoral scholar in electrical engineering at Stanford and co-lead author of a study published in the Dec. 9 edition of Nature Communications. “That is the promise of TMDs.”

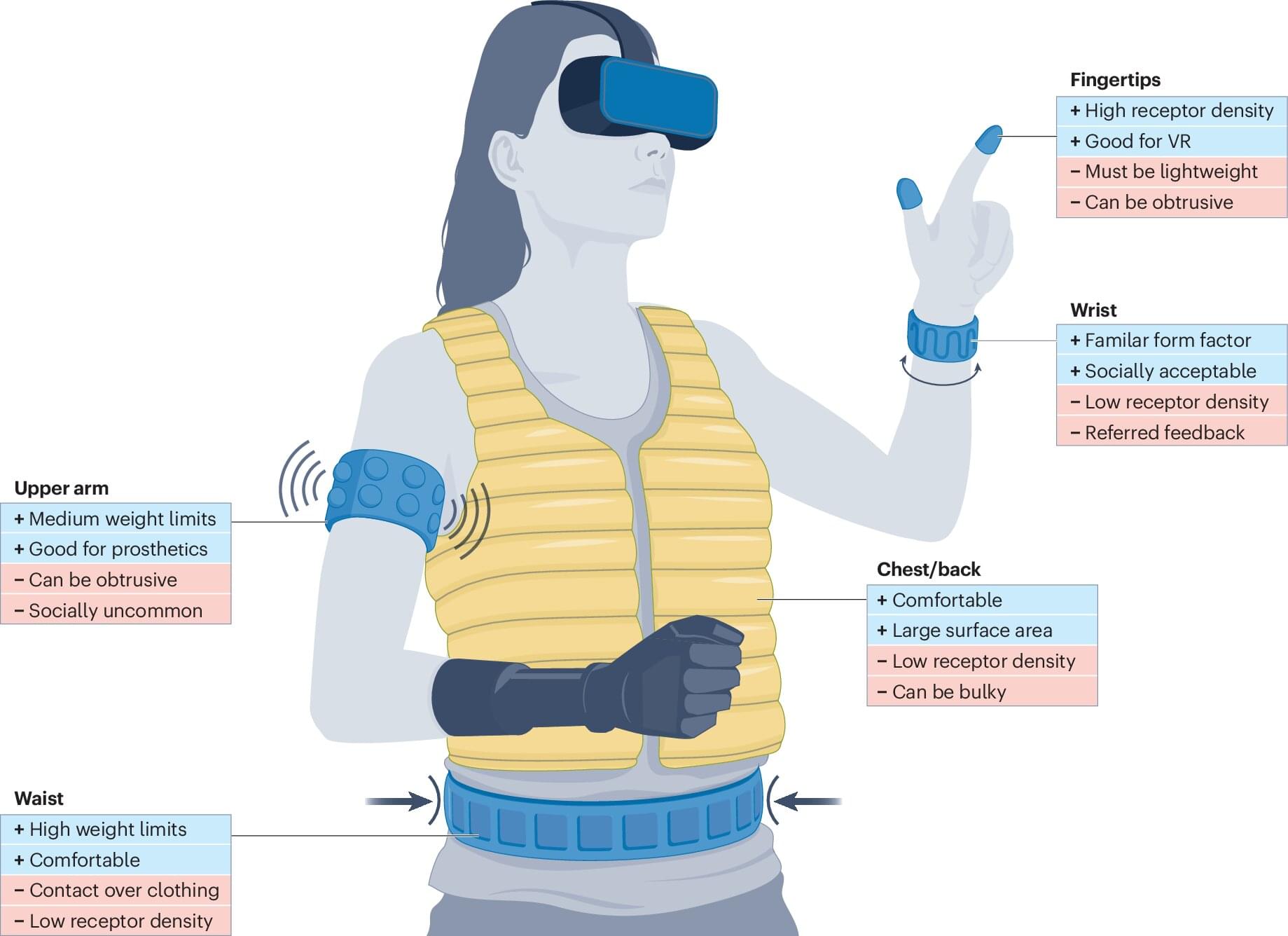

The search for new materials is necessary because the reigning king of solar materials, silicon, is much too heavy, bulky and rigid for applications where flexibility, lightweight and high power are preeminent, such as wearable devices and sensors or aerospace and electric vehicles.

New, ultrathin photovoltaic materials could eventually be used in mobile applications, from self-powered wearable devices and sensors to lightweight aircraft and electric vehicles.