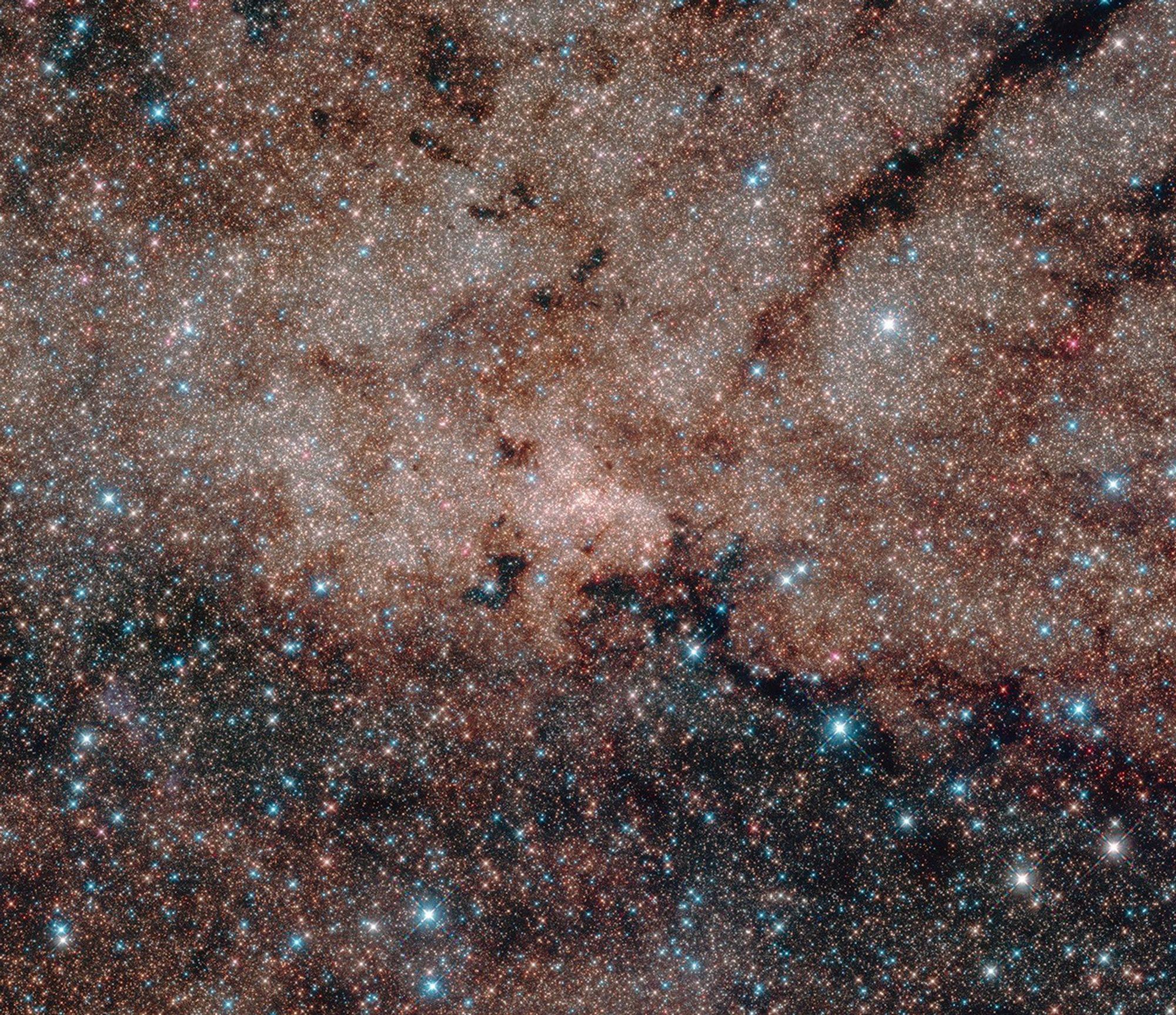

What can merging star clusters teach scientists about the formation and evolution of dwarf galaxies, which are smaller galaxies than our Milky Way and orbi | Space

Category: evolution

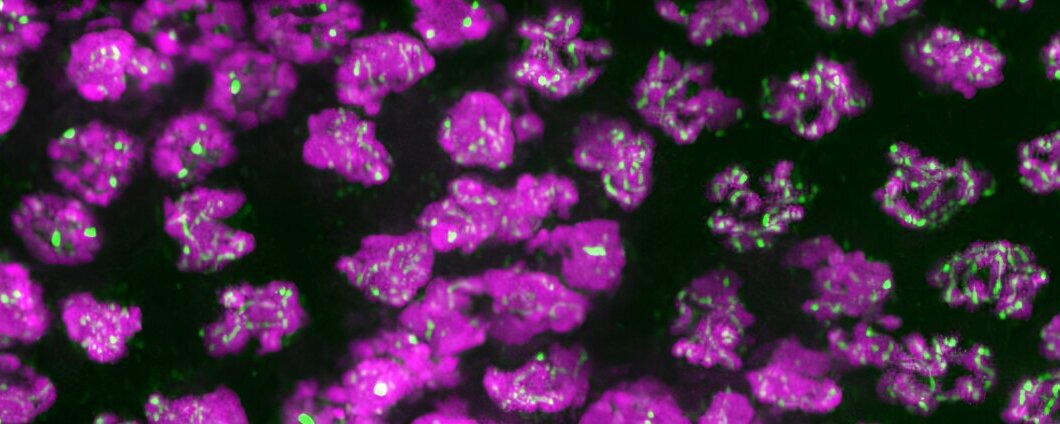

The biological research of UC Santa Cruz’s Needhi Bhalla to determine the molecular motions at the heart of heredity has yielded a new discovery: The proper transfer of genetic materials depends on two key proteins that choreograph the delicate dance between chromosomes when sexual-reproduction cells divide.

When cells split to create eggs and sperm, they must undergo a crucial process called “meiotic crossover recombination.” This mechanism ensures that genetic material is properly shuffled between chromosomes, preventing errors that could lead to disorders such as miscarriages, infertility, birth defects, and even cancer.

This process also results in the endearing transfer of traits that parents see in their children. And beyond contributing to parental pride, Bhalla says meiotic crossover recombination is fundamental for human evolution by promoting genetic diversity. That’s why the identification of two specific proteins that play central roles in controlling how and where these crossovers happen is so significant.

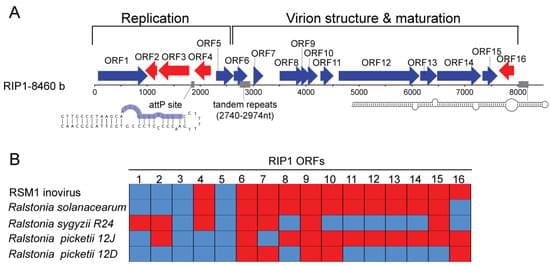

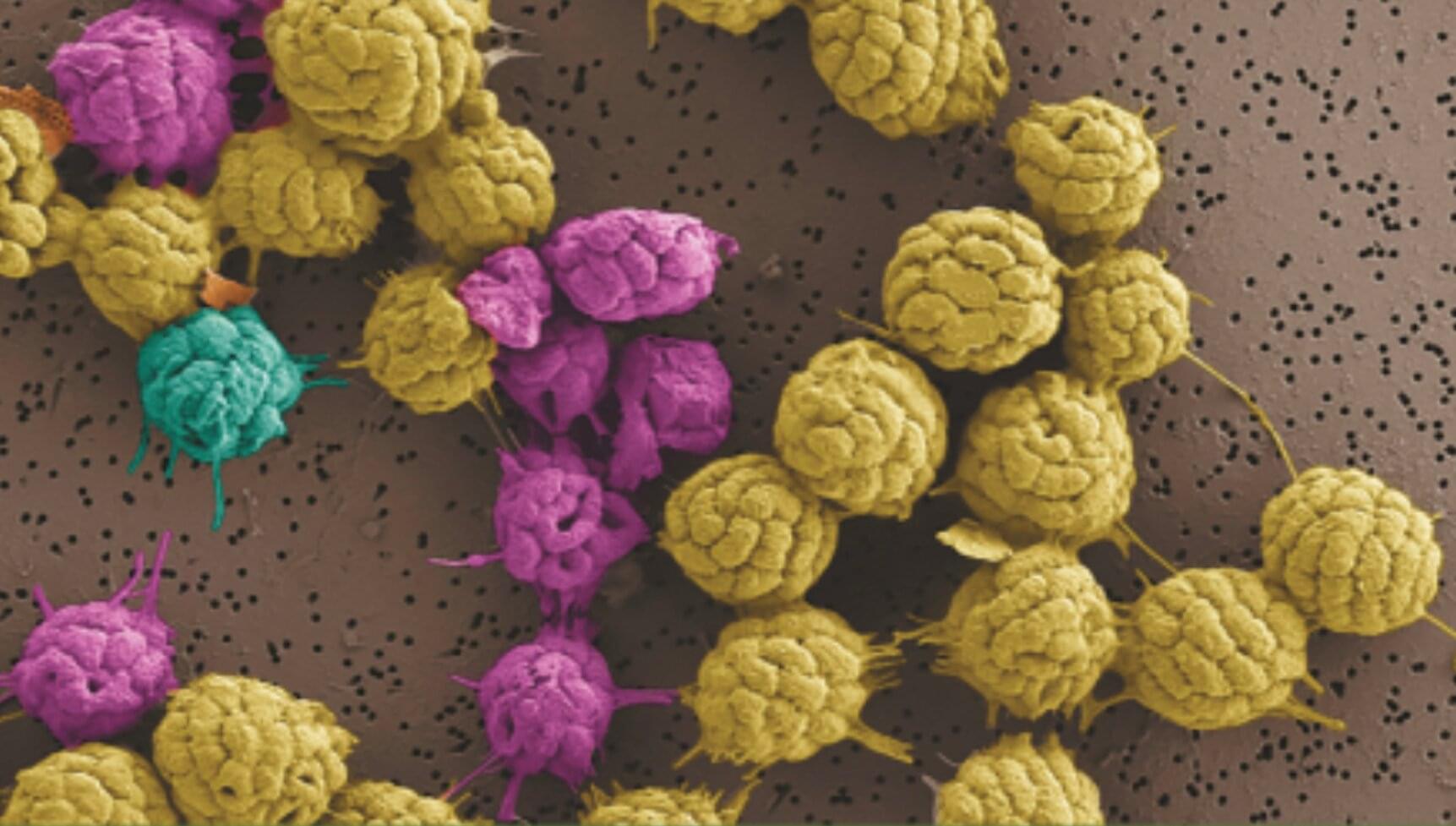

Viruses infecting bacteria (bacteriophages) represent the most abundant viral particles in the human body. They participate in the control of the human-associated bacterial communities and play an important role in the dissemination of virulence genes. Here, we present the identification of a new filamentous single-stranded DNA phage of the family Inoviridae, named Ralstonia Inoviridae Phage 1 (RIP1), in the human blood. Metagenomics and PCR analyses detected the RIP1 genome in blood serum, in the absence of concomitant bacterial infection or contamination, suggesting inovirus persistence in the human blood. Finally, we have experimentally demonstrated that the RIP1-encoded rolling circle replication initiation protein and serine integrase have functional nuclear localization signals and upon expression in eukaryotic cells both proteins were translocated into the nucleus. This observation adds to the growing body of data suggesting that phages could have an overlooked impact on the evolution of eukaryotic cells.

Scientists have discovered a new phylum of microbes in Earth’s Critical Zone, an area of deep soil that restores water quality. Ground water, which becomes drinking water, passes through where these microbes live, and they consume the remaining pollutants. The paper, “Diversification, niche adaptation and evolution of a candidate phylum thriving in the deep Critical Zone,” is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Leonardo da Vinci once said, “We know more about the movement of celestial bodies than about the soil underfoot.” James Tiedje, an expert in microbiology at Michigan State University, agrees with da Vinci. But he aims to change this through his work on the Critical Zone, part of the dynamic “living skin” of Earth.

“The Critical Zone extends from the tops of trees down through the soil to depths up to 700 feet,” Tiedje said. “This zone supports most life on the planet as it regulates essential processes like soil formation, water cycling and nutrient cycling, which are vital for food production, water quality and ecosystem health. Despite its importance, the deep Critical Zone is a new frontier because it’s a major part of Earth that is relatively unexplored.”

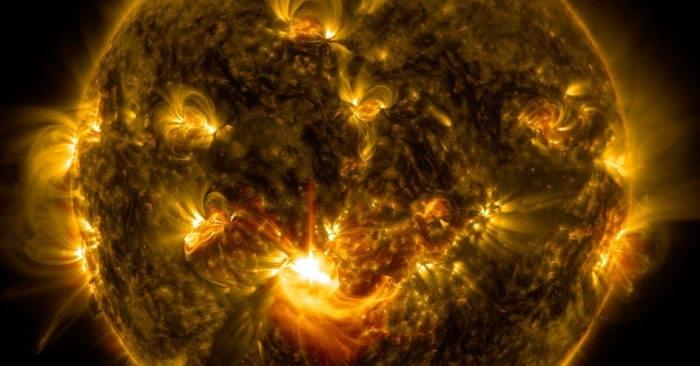

Astronomers using the James Webb Space Telescope have discovered the most distant quiescent galaxy ever seen – one that had already stopped forming stars just 700 million years after the Big Bang. This challenges existing models of galaxy evolution, which can’t explain how such massive, red and

New research suggests that Earth’s first crust, formed over 4.5 billion years ago, already carried the chemical traits we associate with modern continents. This means the telltale fingerprints of continental crust didn’t need plate tectonics to form, turning a long-standing theory on its head.

Using simulations of early Earth conditions, scientists found that the intense heat and molten environment of the planet’s infancy created these signatures naturally. The finding shakes up how we understand Earth’s evolution and could even influence how we think about crust formation on other planets.

A surprising shift in earth’s history.

UNSW researchers interrogated the ‘sounds’ of a cluster of stars within the Milky Way, uncovering a new technique for astrophysicists to probe the universe and learn more about its evolution.

A new suggestion that complexity increases over time, not just in living organisms but in the nonliving world, promises to rewrite notions of time and evolution.

In a recent study, researchers gained new insight into the lives of bacteria that survive by grouping together as if they were a multicellular organism. The organisms in the study are the only bacteria known to do this in this way, and studying them could help astrobiologists explain important steps in the evolution of life on Earth.

The work is published in the journal PLOS Biology.

The organisms in the study are known as multicellular magnetotactic bacteria (MMB). Being magnetotactic means that MMB are part of a select group of bacteria that orient their movement based on Earth’s magnetic field using tiny “compass needles” in their cells. As if that weren’t special enough, MMB also live bunched up in collections of cells that are considered by some scientists to exhibit “obligate” multicellularity, the trait on which the new study is focused.

Some stars in our galaxy pulse like musical instruments, and scientists have found a way to listen in. These rhythmic starquakes, like vibrations in a string or drum, reveal vital clues about a star’s age, composition, and life cycle.

By studying these “melodies” in a star cluster called M67—whose stars are like solar siblings—researchers uncovered a strange pause in stellar evolution called the “plateau.” This discovery helps pinpoint stellar ages with remarkable precision, bringing us closer to understanding how stars, and ultimately our galaxy, have evolved.

Celestial Music: Listening to Starquakes.