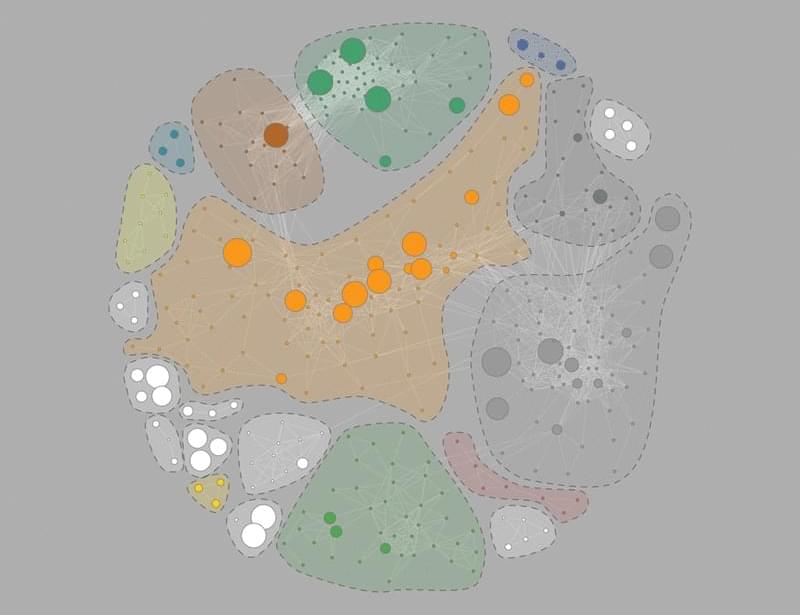

A new brain-inspired AI model called TopoLM learns language by organizing neurons into clusters, just like the human brain. Developed by researchers at EPFL, this topographic language model shows clear patterns for verbs, nouns, and syntax using a simple spatial rule that mimics real cortical maps. TopoLM not only matches real brain scans but also opens new possibilities in AI interpretability, neuromorphic hardware, and language processing.

Join our free AI content course here 👉 https://www.skool.com/ai-content-acce… the best AI news without the noise 👉 https://airevolutionx.beehiiv.com/ 🔍 What’s Inside: • A brain-inspired AI model called TopoLM that learns language by building its own cortical map • Neurons are arranged on a 2D grid where nearby units behave alike, mimicking how the human brain clusters meaning • A simple spatial smoothness rule lets TopoLM self-organize concepts like verbs and nouns into distinct brain-like regions 🎥 What You’ll See: • How TopoLM mirrors patterns seen in fMRI brain scans during language tasks • A comparison with regular transformers, showing how TopoLM brings structure and interpretability to AI • Real test results proving that TopoLM reacts to syntax, meaning, and sentence structure just like a biological brain 📊 Why It Matters: This new system bridges neuroscience and machine learning, offering a powerful step toward *AI that thinks like us. It unlocks better interpretability, opens paths for **neuromorphic hardware*, and reveals how one simple principle might explain how the brain learns across all domains. DISCLAIMER: This video covers topographic neural modeling, biologically-aligned AI systems, and the future of brain-inspired computing—highlighting how spatial structure could reshape how machines learn language and meaning. #AI #neuroscience #brainAI

Get the best AI news without the noise 👉 https://airevolutionx.beehiiv.com/

🔍 What’s Inside:

• A brain-inspired AI model called TopoLM that learns language by building its own cortical map.

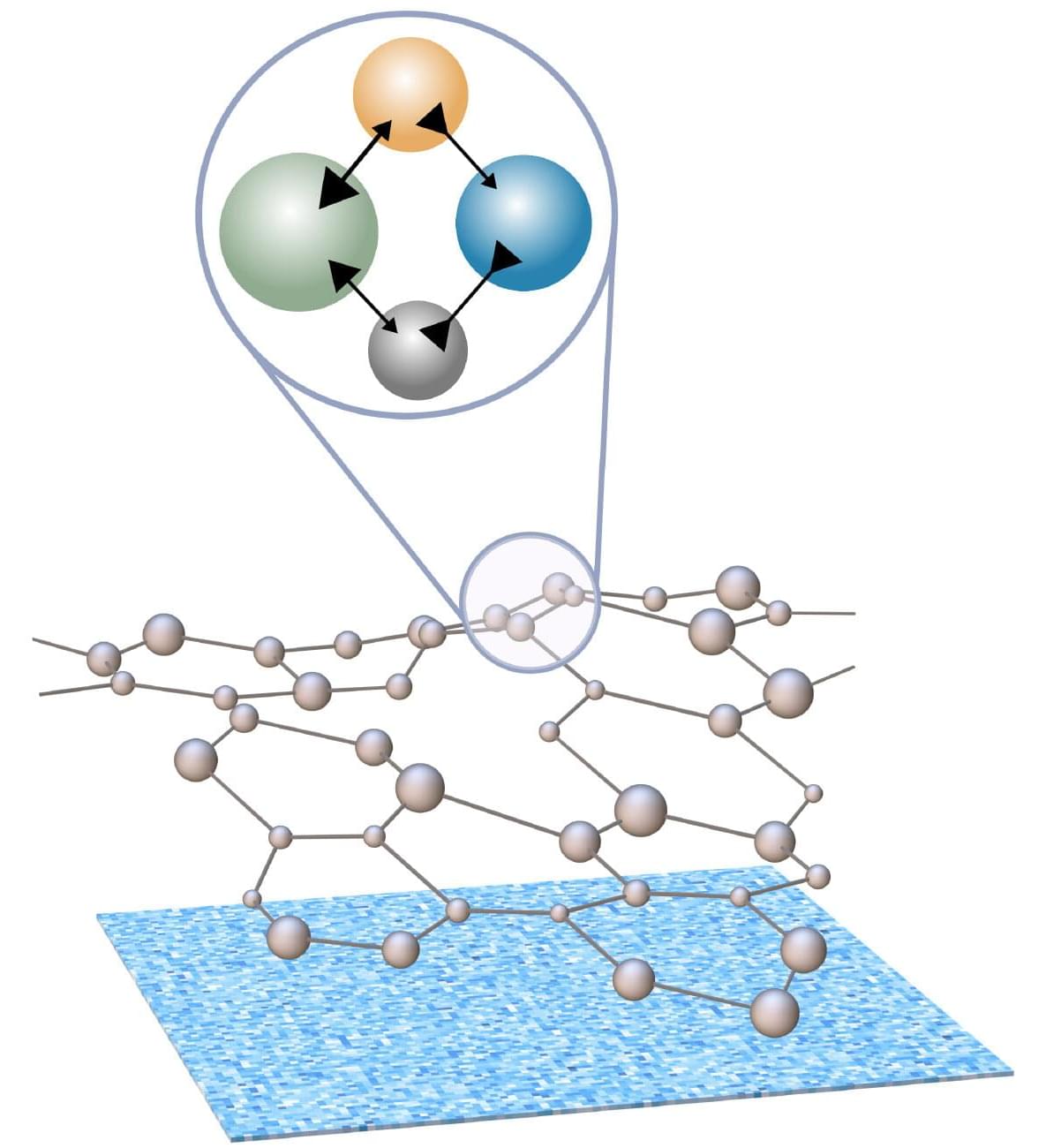

• Neurons are arranged on a 2D grid where nearby units behave alike, mimicking how the human brain clusters meaning.

• A simple spatial smoothness rule lets TopoLM self-organize concepts like verbs and nouns into distinct brain-like regions.

🎥 What You’ll See:

• How TopoLM mirrors patterns seen in fMRI brain scans during language tasks.

• A comparison with regular transformers, showing how TopoLM brings structure and interpretability to AI

• Real test results proving that TopoLM reacts to syntax, meaning, and sentence structure just like a biological brain.

📊 Why It Matters: