What are the potential health risks from airborne dust pollution, especially in the growing threat of climate change? This is what a recent study published | Earth And The Environment

Category: climatology

Reports of extraterrestrial beings, particularly the iconic “grey aliens,” have permeated modern folklore and ufology since the mid-20th century. These beings — typically described as small-statured humanoids with large, black almond-shaped eyes, diminutive noses and mouths, and grey skin — have become embedded in our cultural consciousness (Sagan, 1995). But what if these entities are not visitors from distant stars, but rather glimpses of our own evolutionary future? This essay explores a compelling hypothesis: that the grey aliens reported in countless encounters might be evolved or bio-engineered humans from our future, adapted specifically for subterranean existence following a global catastrophe.

Humanity stands at a crossroads of existential risk. Climate change, nuclear proliferation, biological warfare capabilities, and ecological collapse represent just a few of the potential calamities that could force a dramatic reshaping of human civilization (Bostrom, 2013). If surface conditions on Earth became inhospitable — whether through nuclear winter, extreme solar radiation following ozone depletion, or uninhabitable surface temperatures — surviving populations might be driven underground, initiating a profound evolutionary divergence.

“When faced with extinction-level threats, species often undergo rapid adaptation to secure their survival,” notes evolutionary biologist Dr. Elena Rodriguez (2022, p. 87). “Humans, with their capacity for technological intervention in their own biology, could potentially accelerate this process by orders of magnitude.”

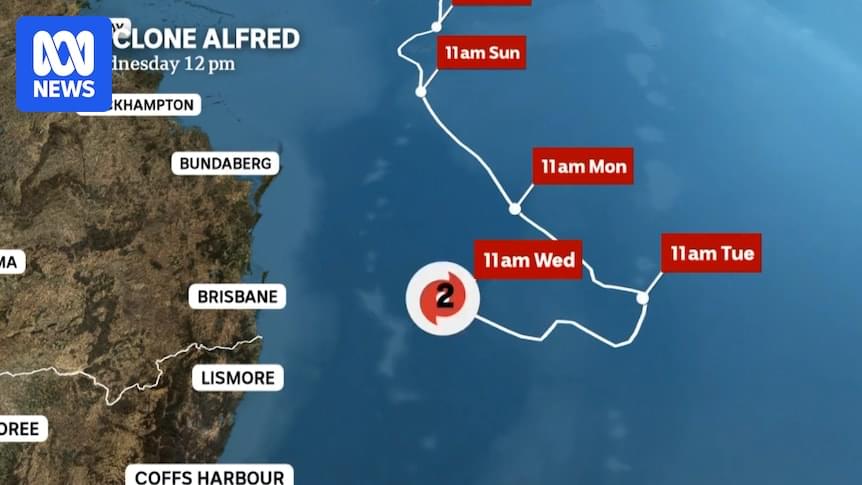

A week before Tropical Cyclone Alfred was nearing the east coast of Australia, most forecasts were favouring a path either well offshore or near the central Queensland coast.

There was a curious anomaly though: an AI prediction from Google’s DeepMind, called Graphcast, was predicting the centre of Alfred would be just 200 kilometres off the coast of Brisbane.

That forecast, made 12 days before ex-Tropical Cyclone Alfred crossed the south-east Queensland coast, was far more accurate than leading weather models used by meteorological organisations around the world, including our own Bureau of Meteorology (BOM).

Copper is the mineral most fundamental to the human future because it is essential to electricity generation, distribution, and storage. Copper availability and demand determine the rate of electrification, which is the foundation of current climate policy. Many studies have raised concerns that copper supply cannot meet the copper demands of both the green energy transition and equitable global development, but the seemingly universal presumption persists that the copper needed for the green transition will somehow be available. This need not be the case for even the first step of vehicle electrification.

This paper addresses this issue by projecting copper supply and demand from 2018 to 2050 and placing both in the historical context of copper mine output. Discussion is focused on a single diagram that illustrates the unprecedented nature of the copper mining challenge and ways to reduce copper demand.

Just to meet business-as-usual trends, 115% more copper must be mined in the next 30 years than has been mined historically until now. To electrify the global vehicle fleet requires bringing into production 55% more new mines than would otherwise be needed. On the other hand, hybrid electric vehicle manufacture would require negligible extra copper mining.

Among the mountains of evidence that climate change is warming Earth faster than any other point in recorded history is the fact that most glaciers around the world are shrinking or disappearing. Melting glaciers and ice sheets are already the biggest contributors to global sea level rise, and according to the World Glacier Monitoring Service, ice loss rates have increased each decade since 1970. Yet, of the approximately 200,000 glaciers in the world currently, no database exists to identify which glaciers have disappeared, and when. The Global Land Ice Measurements from Space (GLIMS) initiative, an international project designed to monitor the world’s glaciers primarily using data from optical satellite instruments, aims to change that.

“Glaciers are indicators of climate change because they grow and shrink on longer timescales than rapidly changing weather, so they give a clearer signal about climate,” said Bruce Raup, a senior associate scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) and director of the GLIMS initiative. “We know that glaciers are disappearing, but we’ve had no way to show that to people. So, we are making an effort to document glaciers that have disappeared and approximately when they disappeared.”

Don’t judge space junk’s potential for destruction using your Earthly instincts: Traveling at tens of thousands of miles per hour in space, even a small object has the potential to inflict major damage. In one incident that demonstrates that fact of physics, a 2mm piece of space once junk put a 5cm-wide dent in a climate satellite. A modest move up the scale brings much more power: “A one-centimeter piece of debris has the energy of a hand grenade,” ESA’s Tiago Soares told DW.

In an ominous 2009 incident, a Russian Cosmos satellite collided with an Iridium satellite, creating a cloud of about 2,000 pieces of junk measuring 10cm or more. That’s brings us to the nightmare scenario that should fill you with dread: The Kessler Effect. Imagine an initial major impact that creates hundreds of shards, which then start colliding with more orbiting objects, setting off a chain reaction. Actually, you don’t need your imagination. While some scientists say it wasn’t fully accurate in depicting the physics, Hollywood ventured to depict the Kessler Effect in the 2013 movie, Gravity:

The world added the smallest amount of new coal capacity in two decades last year, a report said Thursday, but use of the fossil fuel is still surging in China and India.

Coal accounts for just over a third of global electricity production and phasing it out is fundamental to meeting climate change goals.

Just 44 gigawatts (GW) of new coal power capacity was produced globally last year, the lowest figure since 2004, according to the report by a group of energy-and environment-focused research organizations and NGOs.

The European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) has fully operationalized its AI Forecasting System (AIFS), achieving up to 20% greater accuracy than traditional methods, particularly in tropical cyclone tracking.

A new study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences has turned traditional thinking on its head by highlighting the role of human interactions during the shift from hunting and gathering to farming—one of the biggest changes in human history—rather than earlier ideas that focused on environmental factors.

The transition from a hunter-gatherer foraging lifestyle, which humanity had followed for hundreds of thousands of years, to a settled farming one about 12,000 years ago has been widely discussed in popular books like “Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind” by Yuval Noah Harari.

Researchers from the University of Bath, the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany, the University of Cambridge, UCL, and others have developed a new mathematical model that challenges the traditional view that this major transition was driven by external factors, such as climate warming, increased rainfall, or the development of fertile river valleys.

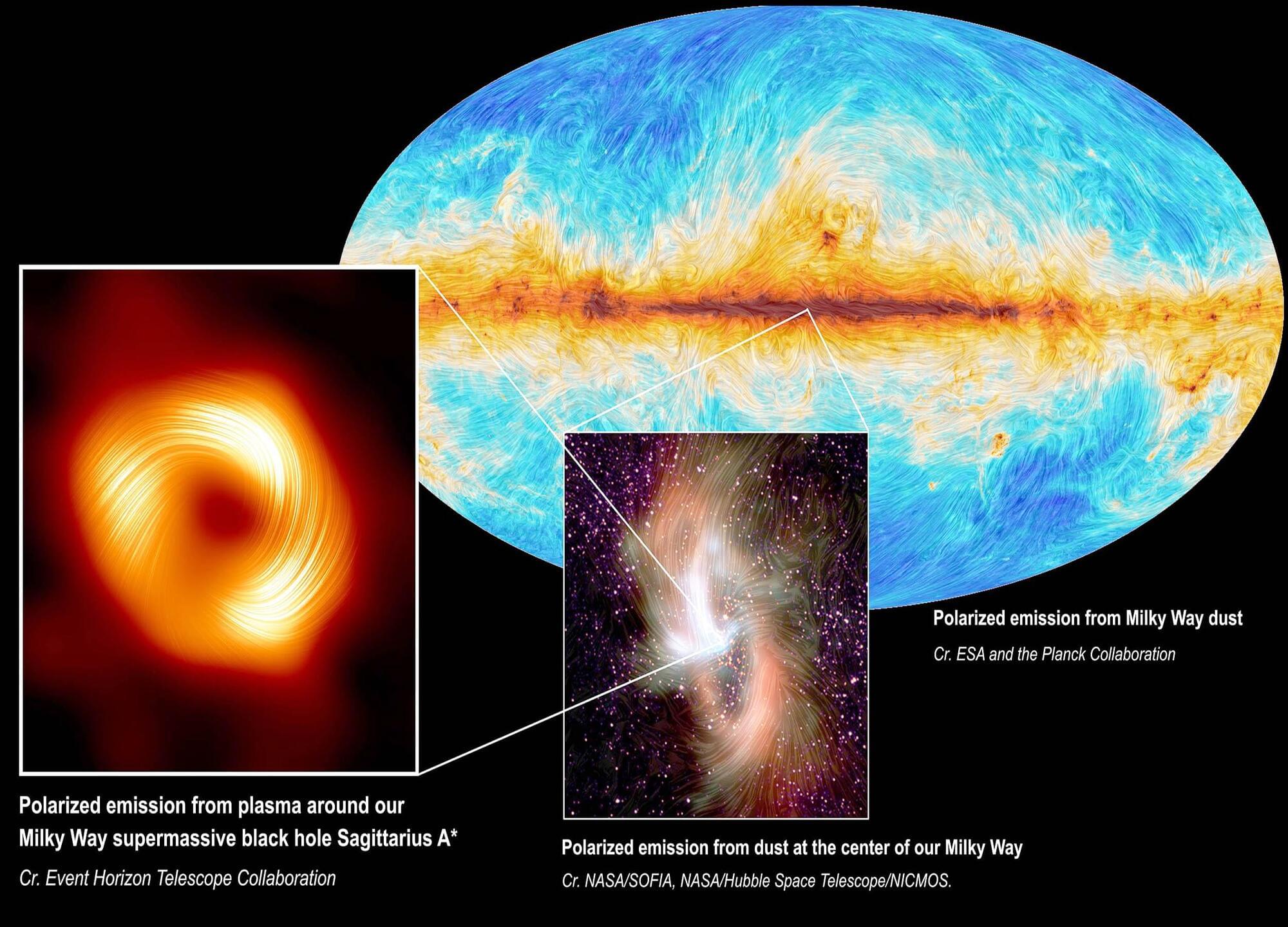

Deep in the galaxy’s central molecular zone (CMZ), surrounding the supermassive black hole at the Milky Way’s center, clouds of dust and gas swirl amid energetic shock waves.

Now, a collaboration of international astronomers – using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) – has greatly sharpened our view of these processes by a factor of 100.

The team has uncovered an unexpected class of long, narrow filaments within this turbulent region, giving fresh insight into the cyclical formation and destruction of material in the CMZ.