Scientists have unveiled a cutting-edge quantum microscope that allows them to observe how electrons interact with strange atomic vibrations in twisted graphene, including a newly revealed “phason.” This phenomenon could help explain mysterious behaviors like superconductivity in materials rotate

Category: quantum physics

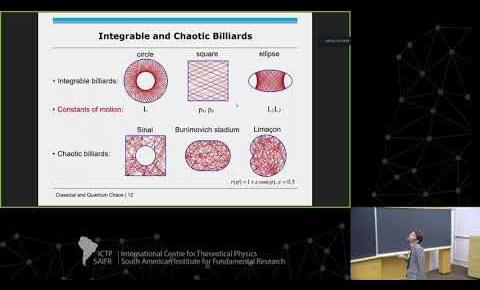

ICTP — SAIFR

School on Quantum Chaos.

August 21 – September 1, 2023

Speaker:

Barbara Dietz (Institute for Basic Science (IBS), Republic of Korea): Non-Relativistic and Relativistic Quantum Chaos.

More Informations:

Paper link : https://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevLett.134.

Chapters:

00:00 Introduction.

00:49 Breaking the Classical Wall – What the Game Revealed.

02:32 Entanglement at Scale – Knots, Topology, and Robust Design.

03:51 Implications – A New Era of Quantum Machines.

07:37 Outro.

07:47 Enjoy.

MUSIC TITLE : Starlight Harmonies.

MUSIC LINK : https://pixabay.com/music/pulses-starlight-harmonies-185900/

Visit our website for up-to-the-minute updates:

www.nasaspacenews.com.

Follow us.

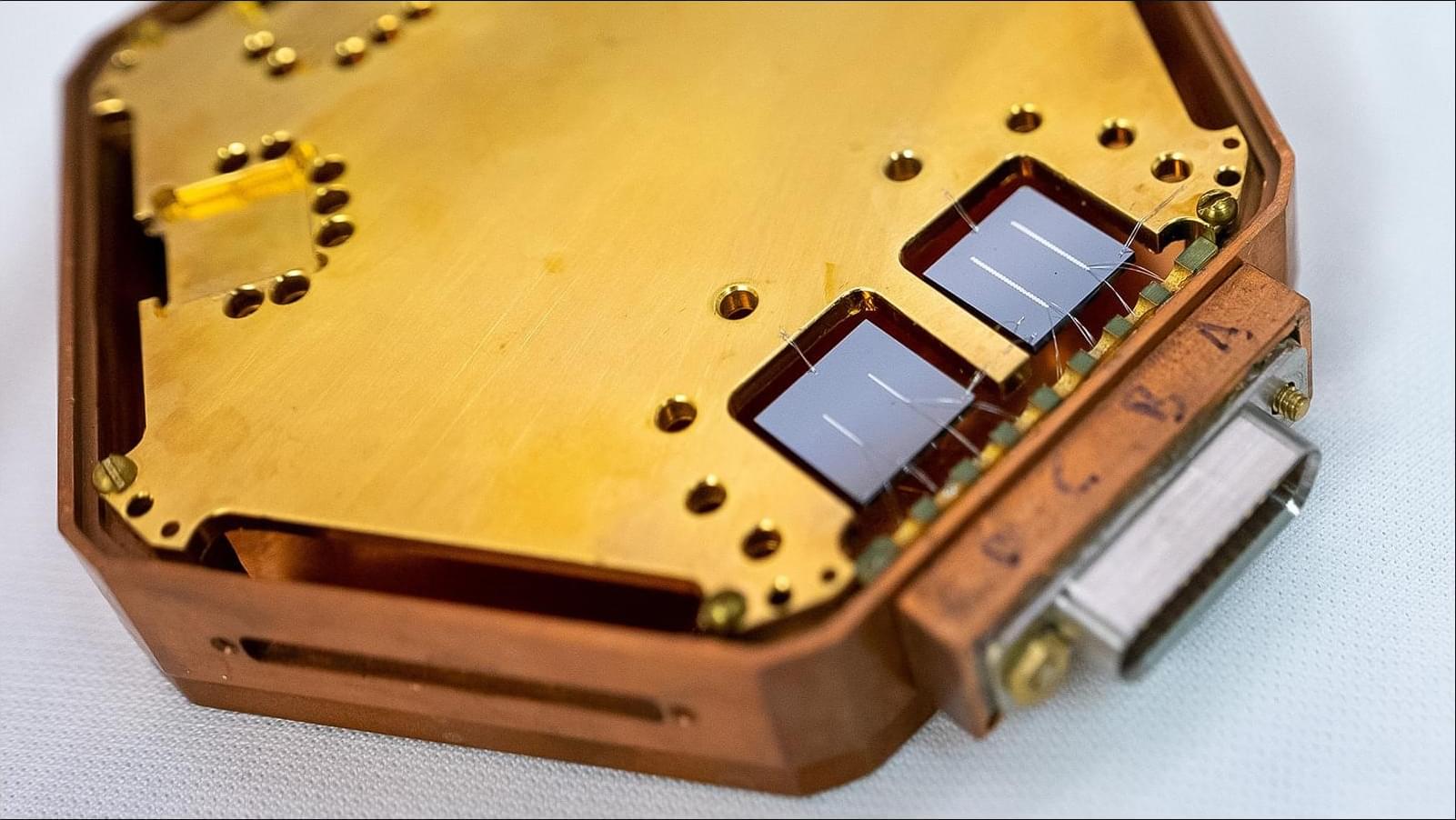

TESSERACT has developed exquisitely sensitive transition-edge sensors that open up new searches for dark matter and have potential applications in quantum computing.

We are surrounded by a multiplicity of materials, from metals and alloys to crystals, glasses, and ceramics; from polymers and plastics to organic and living-derived substances; and let’s not forget natural materials like stone and exotic materials like aerogel.

The amazing thing to me is that all these materials are formed from different combinations of the same small group of elements. For example, while living organisms and other objects can contain traces of many elements, a core group does the heavy lifting; only six elements—carbon ©, hydrogen (H), oxygen (O), nitrogen (N), phosphorus ℗, and sulfur (S)—make up over 95% of the mass of most living things.

Similarly, only eight elements—oxygen (O), silicon (Si), aluminum (Al), iron (Fe), calcium (Ca), Sodium (Na), potassium (K), and magnesium (Mg)—make up more than 98% of the Earth’s crust.

“We’ll See Gravity Like Never Before”: NASA’s Wild Quantum Gradiometer Will Map Earth’s Invisible Forces From Orbit

Posted in particle physics, quantum physics, space | Leave a Comment on “We’ll See Gravity Like Never Before”: NASA’s Wild Quantum Gradiometer Will Map Earth’s Invisible Forces From Orbit

IN A NUTSHELL 🌍 NASA collaborates with private and academic sectors to develop the Quantum Gravity Gradiometer Pathfinder, a revolutionary space-based quantum sensor. ❄️ The gradiometer uses ultra-cold rubidium atoms to measure Earth’s gravitational variations with high precision, free from environmental disturbances. 🔬 Quantum sensors in the QGGPf offer 10 times greater sensitivity and are

To learn more about the nature of matter, energy, space, and time, physicists smash high-energy particles together in large accelerator machines, creating sprays of millions of particles per second of a variety of masses and speeds. The collisions may also produce entirely new particles not predicted by the standard model, the prevailing theory of fundamental particles and forces in our universe. Plans are underway to create more powerful particle accelerators, whose collisions will unleash even larger subatomic storms. How will researchers sift through the chaos?

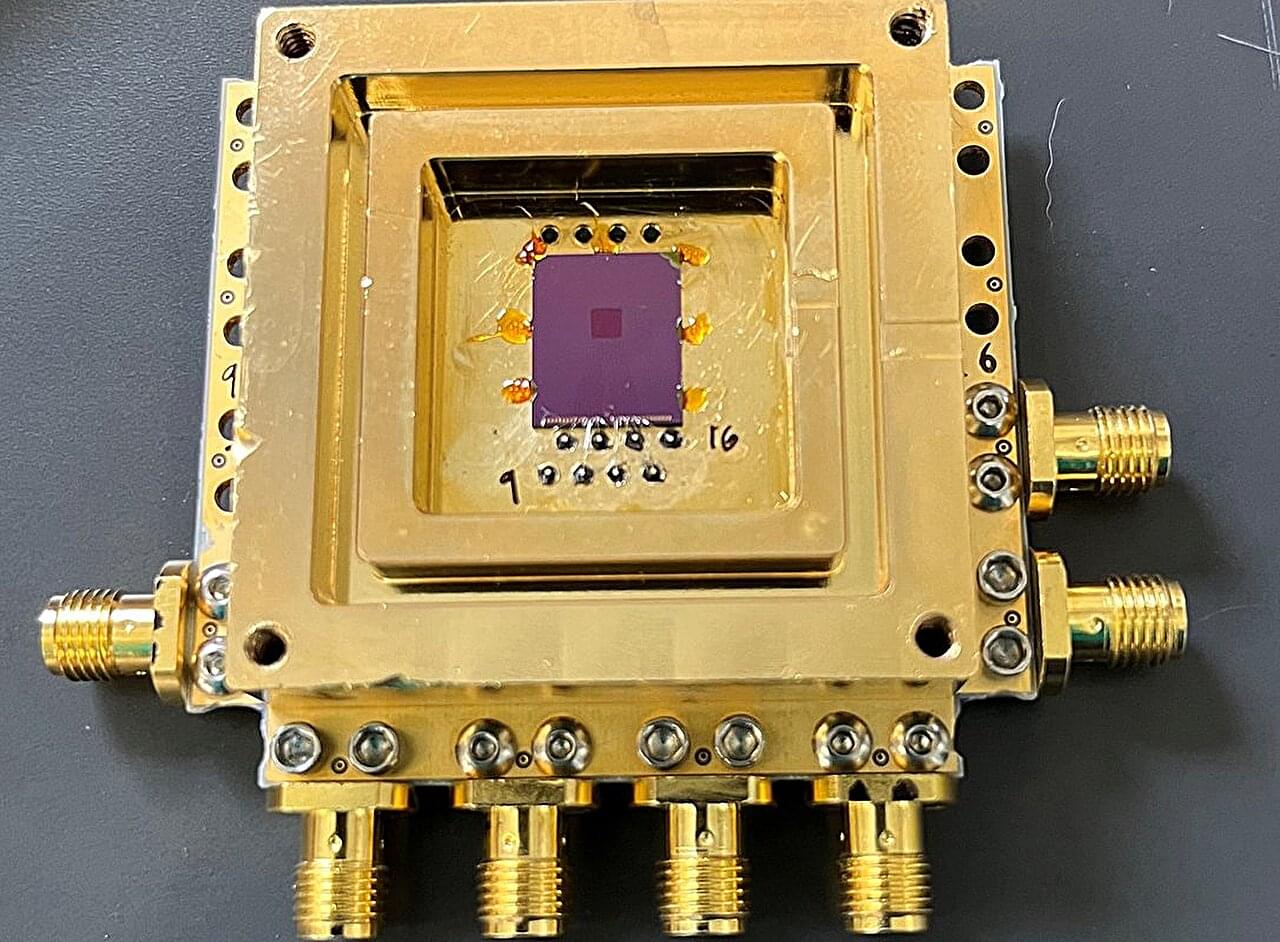

The answer may lie in quantum sensors. Researchers from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab), Caltech, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (which is managed by Caltech), and other collaborating institutions have developed a novel high-energy particle detection instrumentation approach that leverages the power of quantum sensors—devices capable of precisely detecting single particles.

“In the next 20 to 30 years, we will see a paradigm shift in particle colliders as they become more powerful in energy and intensity,” says Maria Spiropulu, the Shang-Yi Ch’en Professor of Physics at Caltech.

This idea puts a morbid twist on quantum theory, suggesting that a copy of you may remain alive, no matter what.

However, when photons are contained within structures that are smaller than their wavelength, these measures collapse into each other, and so the definition is of total angular momentum (TAM). It’s this feature, only occurring for photons confined in this way, that has now been entangled for the first time.

Researchers at Technion-Israel Institute of Technology used gratings to confine photons within a circular or spiral nanoscale platform and mapped their states, entangling the TAMs of pairs of photons before scattering them to free space. Entangling TAMs might seem like a minor development, seeing that SAMs and OAMs have each been entangled before, but the authors write: “We observe that entanglement in TAM leads to a completely different structure of quantum correlations of photon pairs, compared with entanglement related to the two constituent angular momenta.”

Quantum entanglement is considered key to quantum computing. The authors propose their work could lead to information processing conducted using the entangled TAMs of photons confined to chips. Entangling TAMs allows quantum processors based around photons to be smaller than would be possible if one of the properties that only emerges under less confined conditions was used. That potentially enables the miniaturization of future quantum computers.

This book dives into the holy grail of modern physics: the union of quantum mechanics and general relativity. It’s a front-row seat to the world’s brightest minds (like Hawking, Witten, and Maldacena) debating what reality is really made of. Not casual reading—this is heavyweight intellectual sparring.

☼ Key Takeaways:

✅ Spacetime Is Not Continuous: It might be granular at the quantum level—think “atoms of space.”

✅ Unifying Physics: String theory, loop quantum gravity, holography—each gets a say.

✅ High-Level Debates: This is like eavesdropping on the Avengers of physics trying to fix the universe.

✅ Concepts Over Calculations: Even without equations, the philosophical depth will bend your brain.

✅ Reality Is Weirder Than Fiction: Quantum foam, time emergence, multiverse models—all explored.

This isn’t a how-to; it’s a “what-is-it?” If you’re obsessed with the ultimate structure of reality, this is your fix.

☼ Thanks for watching! If the idea of spacetime being pixelated excites you, drop a comment below and subscribe for more mind-bending content.