UPTON, N.Y. — High temperatures and ionizing radiation create extremely corrosive environments inside a nuclear reactor. To design long-lasting reactors, scientists must understand how radiation-induced chemical reactions impact structural materials. Chemists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory and Idaho National Laboratory recently performed experiments showing that radiation-induced reactions may help mitigate the corrosion of reactor metals in a new type of reactor cooled by molten salts. Their findings are published in the journal Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics.

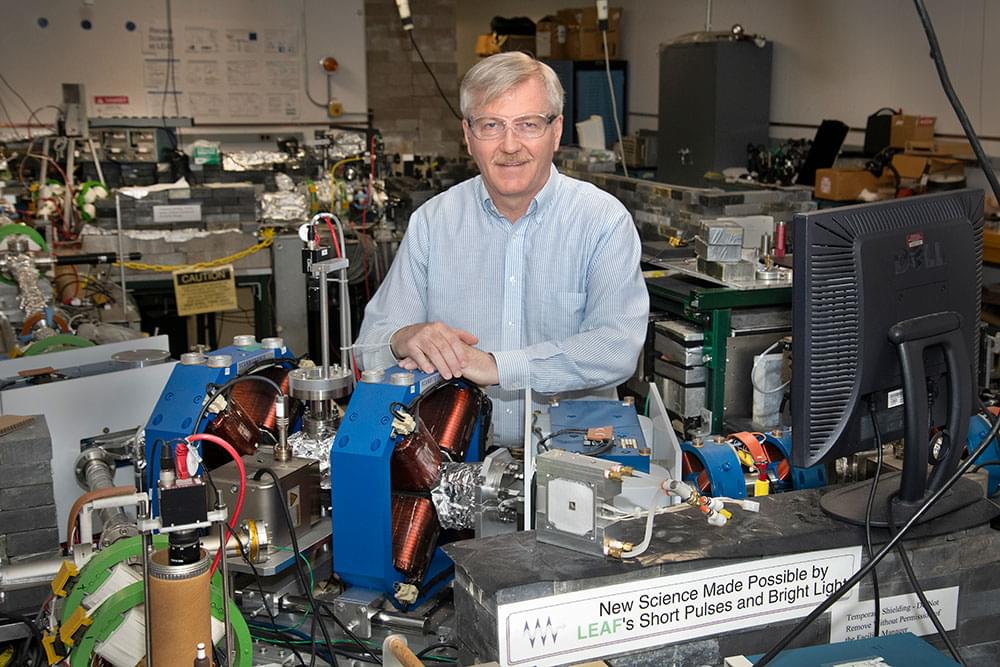

“Molten salt reactors are an emerging technology for safer, scalable nuclear energy production. These advanced reactors can operate at higher, more efficient temperatures than traditional water-cooled reactor technologies while maintaining relatively ambient pressure,” explained James Wishart, a distinguished chemist at Brookhaven Lab and leader of the research.

Unlike water-cooled reactors, molten salt reactors use a coolant made entirely of positively and negatively charged ions, which remain in a liquid state only at high temperatures. It’s similar to melting table salt crystals until they flow without adding any other liquid.