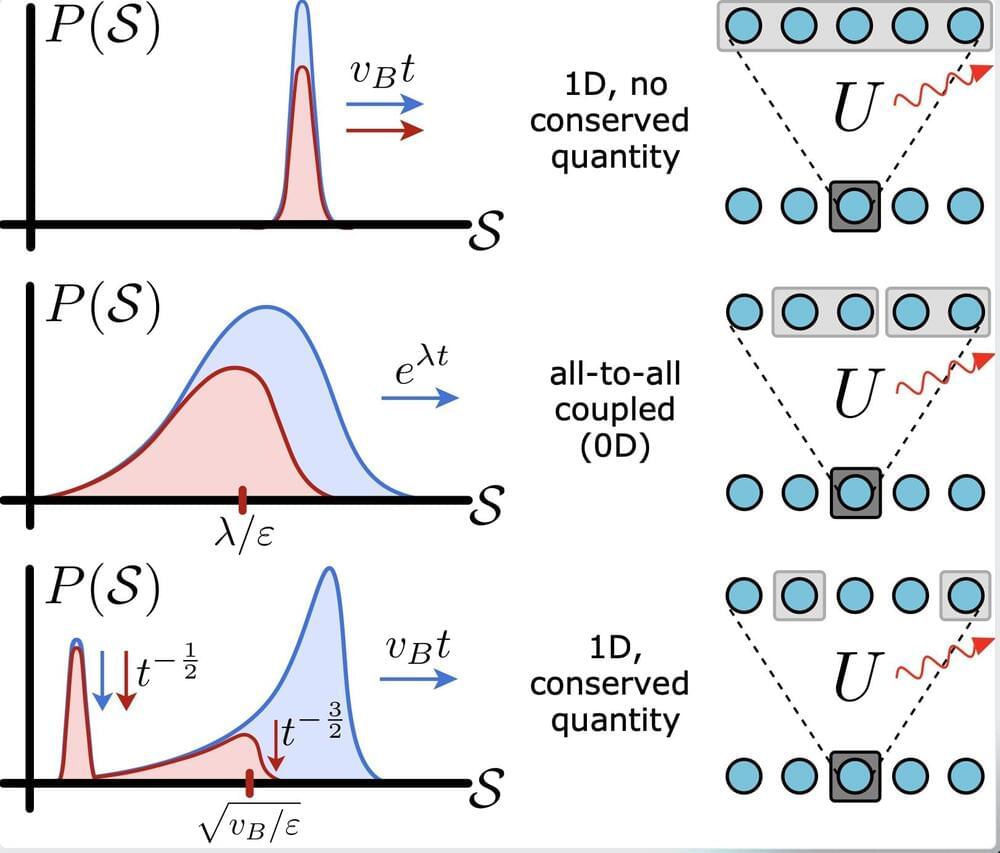

Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle limits the precision with which two observables that do not commute with each other can be simultaneously measured. The Wigner-Araki-Yanase (WAY) theorem goes further. If observables A and B do not commute, and if observable A is conserved, observable B cannot be measured with arbitrary precision even if A is not measured at all. In its original 1960 formulation, the WAY theorem applied only to observables, such as spin, whose possible values are discrete and bounded. Now Yui Kuramochi of Kyushu University and Hiroyasu Tajima of the University of Electro-Communications—both in Japan—have proven that the WAY theorem also encompasses observables, such as position, that are continuous and unbounded [1]. Besides resolving the decades-long problem of how to deal with such observables, the extension will likely find practical applications in quantum optics.

The difficulty of extending the WAY theorem arose from how an unbounded observable L is represented: as an infinite-dimensional matrix with unbounded eigenvalues. To tame the problem, Kuramochi and Tajima avoided considering L directly. Instead, they looked at an exponential function of L, which forms a one-parameter unitary group. Although the exponential function is also unbounded, its spectrum of eigenvalues is contained within the complex plane’s unit circle. Thanks to that boundedness, Kuramochi and Tajima could go on to use off-the-shelf techniques from quantum information to complete their proof.

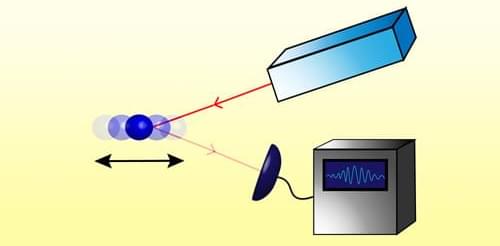

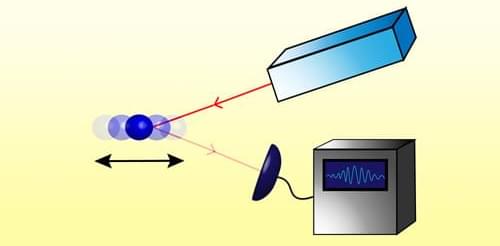

Because momentum is conserved, the extended WAY theorem implies that a particle’s position cannot be measured with arbitrary precision even if its momentum is not measured simultaneously. Similar pairs of observables crop up in quantum optics. Kuramochi and Tajima anticipate that their theorem could be useful in setting limits on the extent to which quantum versions of transmission protocols can outperform the classical ones.