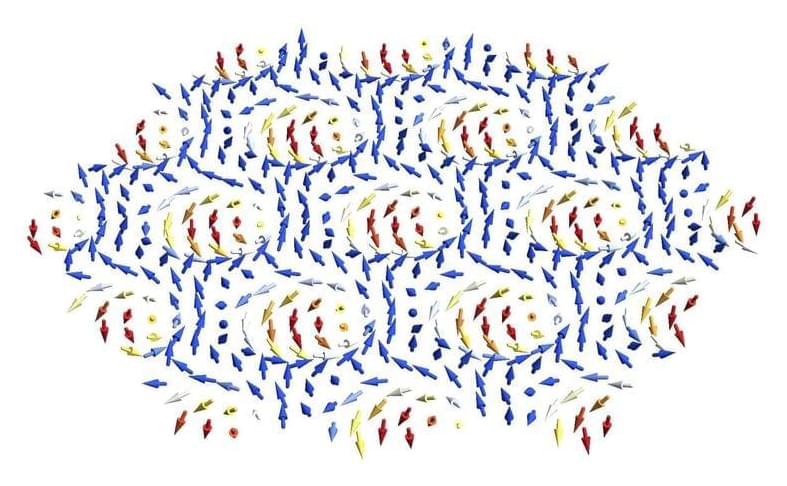

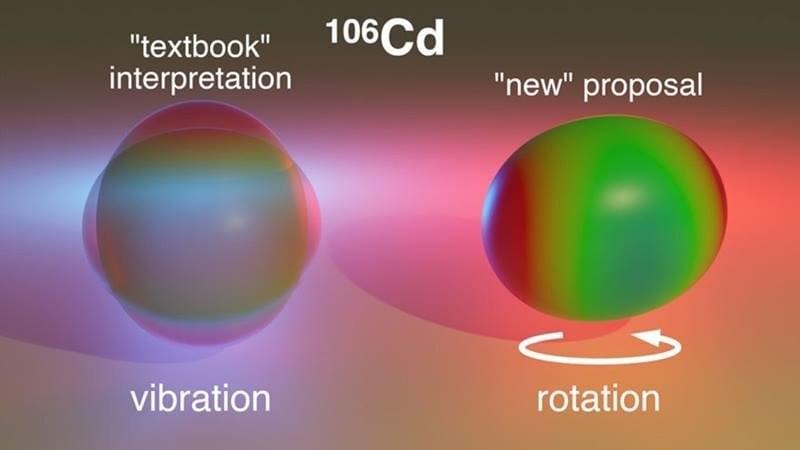

In work that could lead to important new physics with potentially heady applications in computer science and more, MIT scientists have shown that two previously separate fields in condensed matter physics can be combined to yield new, exotic phenomena.

The work is theoretical, but the researchers are excited about collaborating with experimentalists to realize the predicted phenomena. The team includes the conditions necessary to achieve that ultimate goal in a paper published in the February 24 issue of Science Advances.

“This work started out as a theoretical speculation, and ended better than we could have hoped,” says Liang Fu, a professor in MIT’s Department of Physics and leader of the work. Fu is also affiliated with the Materials Research Laboratory. His colleagues are Nisarga Paul, a physics graduate student, and Yang Zhang, a postdoctoral associate who is now a professor at the University of Tennessee.