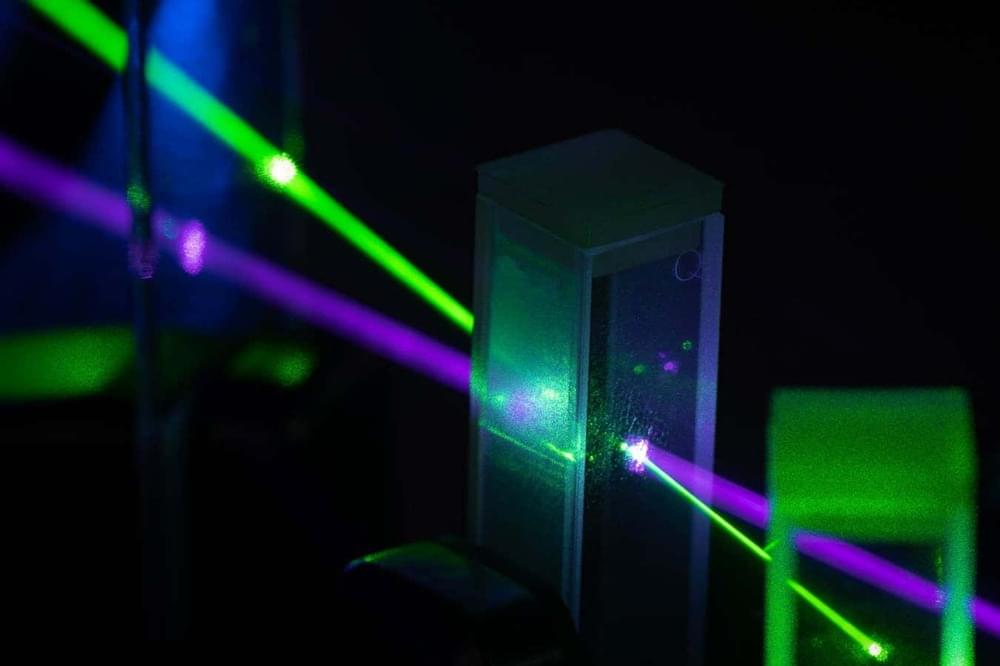

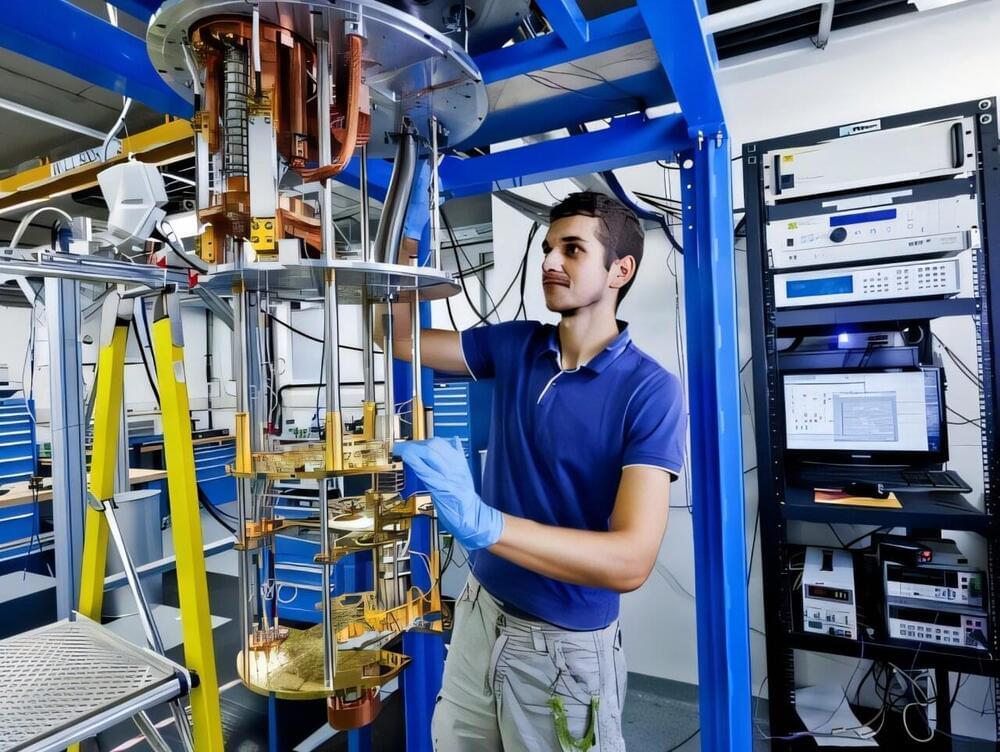

The Higgs boson, often dubbed the “God particle,” has been a focal point of physics since its groundbreaking discovery in 2012. This elusive particle plays a crucial role in our understanding of how elementary particles acquire mass, a concept that has puzzled scientists for decades. But the excitement doesn’t stop there. Seven years after its discovery, new findings from researchers at the Max Planck Institute are taking our knowledge of the Higgs boson to an entirely new level. These advancements promise to unravel deeper mysteries of the universe and open doors to future scientific exploration.

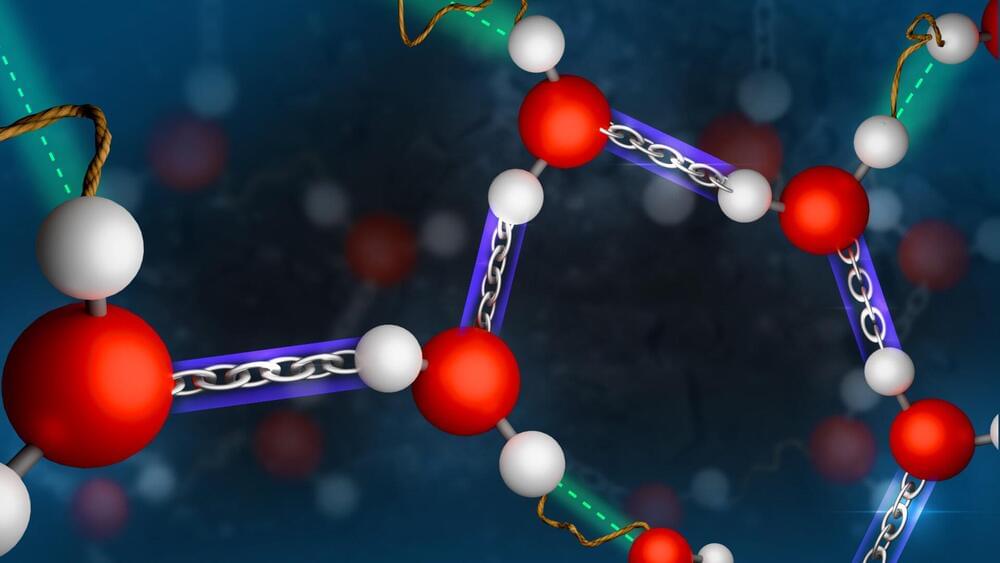

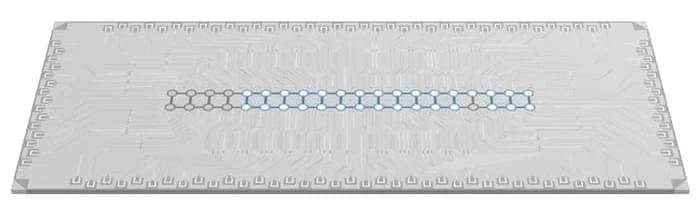

To fully appreciate the recent developments in Higgs boson research, it’s important to revisit the concept of this fundamental particle. In the Standard Model of particle physics, the Higgs boson is the particle responsible for giving mass to other particles. But how exactly does this happen? The answer lies in the Higgs field—a sort of invisible “medium” that permeates the universe, even in a vacuum.

Imagine you’re trying to walk through a swimming pool. When the water is still, you move easily, but if the pool were filled with foam, your movements would slow down considerably. The Higgs field operates similarly, with particles gaining mass as they interact with it, much like how a swimmer would find it harder to move through foam. The more a particle interacts with this field, the more mass it acquires, which allows particles to form the building blocks of matter as we know it.