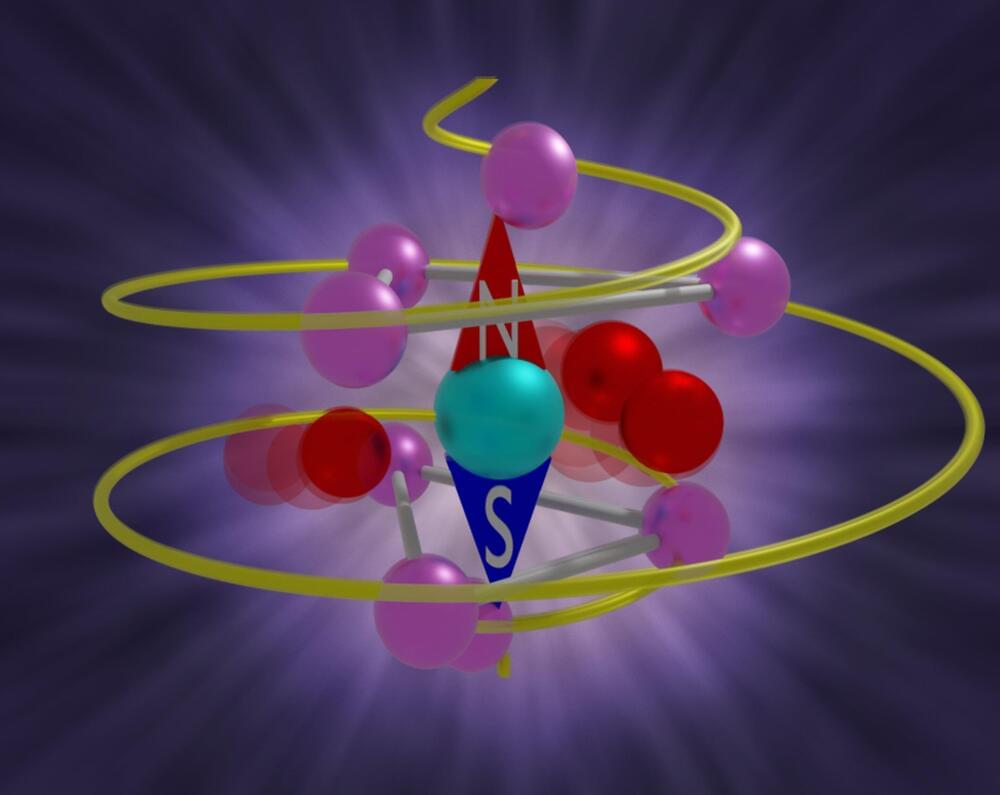

More sophisticated manipulation of complicated materials and their spin states at short time scales will be needed to create the next generation of spintronic devices. But, a thorough understanding of the fundamental physics underpinning nanoscale spin manipulation is necessary to fully utilize these powers for more energy-efficient nanotechnologies.

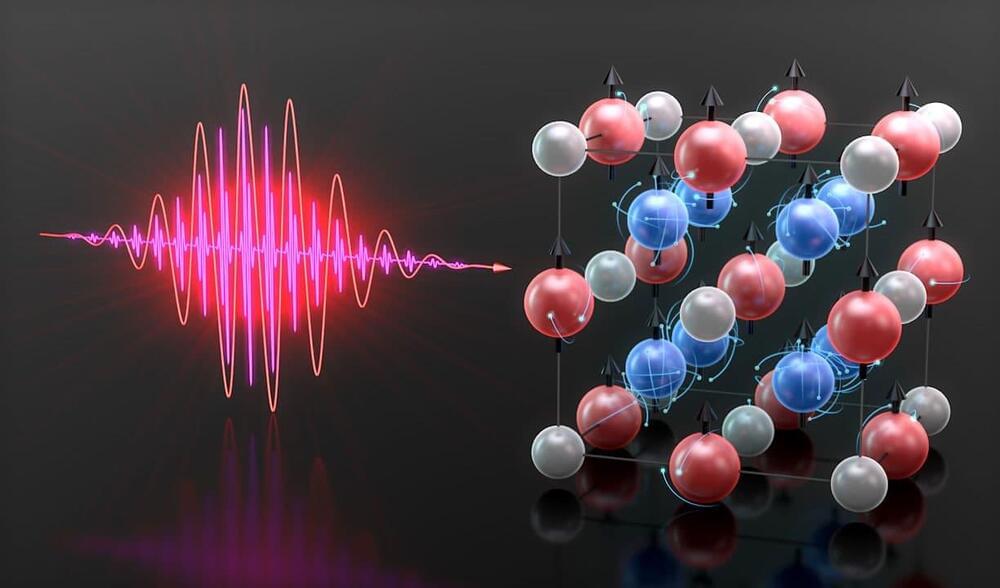

The JILA team and colleagues from institutions in Sweden, Greece, and Germany investigated the spin dynamics within a unique substance known as a Heusler compound—a combination of metals that exhibits properties similar to those of a single magnetic material. In their investigation, the scientists used a cobalt, manganese, and gallium combination that acted as an insulator for electrons with downwardly oriented spins and a conductor for those with upwardly aligned spins.

Scientists used extreme ultraviolet high-harmonic generation (EUV HHG) light as a probe to track the re-orientations of the spins inside the compound after exciting it with a femtosecond laser. Tuning the color of the EUV HHG probe light is the key to accurately interpreting the spin re-orientations.