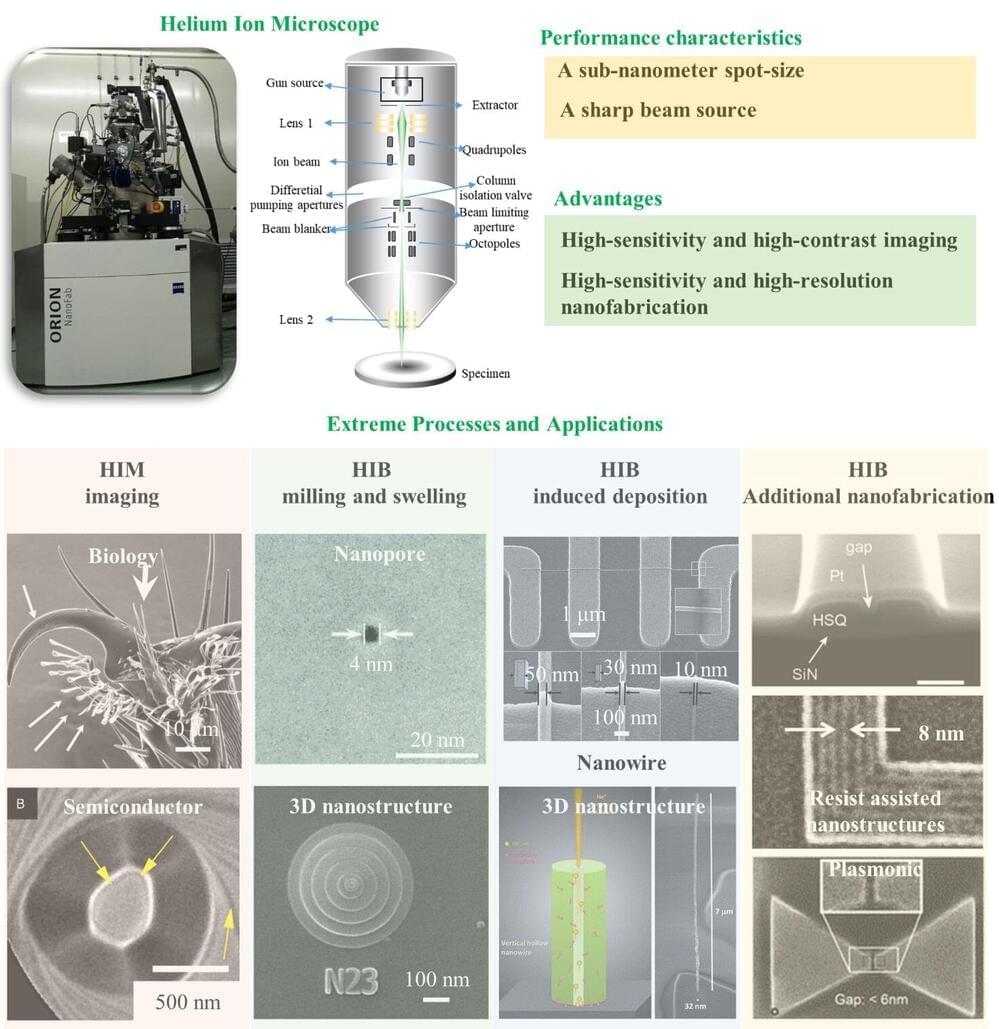

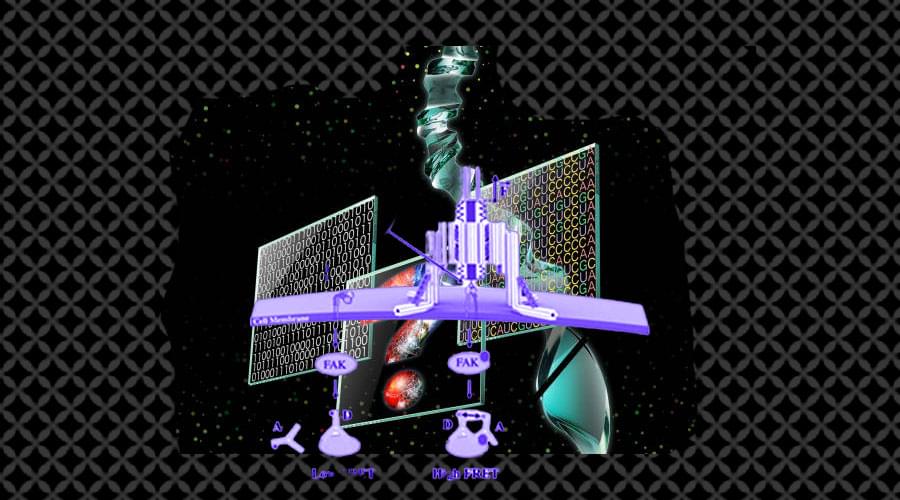

Helium ion beam (HIB) technology plays an important role in the extreme fields of nanofabrication. Due to high resolution and sensitivity, HIB nanofabrication technology is widely used to pattern nanostructures into components, devices, or systems in integrated circuits, materials sciences, nano-optics, and bio-sciences applications. HIB-based nanofabrication includes direct-write milling, ion beam-induced deposition, and direct-write lithography without the need to resist assistance. Their nanoscale applications have also been evaluated in the areas of integrated circuits, materials sciences, nano-optics, and biological sciences.

In a new paper published in the International Journal of Extreme Manufacturing, a team of researchers, led by Dr. Deqiang Wang from Chongqing Key Laboratory of Multi-scale Manufacturing Technology, Chongqing Institute of Green and Intelligent Technology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, PR China, have summarized comprehensively the extreme processes and applications of HIB nanofabrication.

The main aim of this review is to address the latest developments in HIB technology with their extreme processing capabilities and widespread applications in nanofabrication. Based on the introduction of the HIM system with GFIS, the performance characteristics and advantages of HIB technology have been discussed first. Thereafter, certain questions about the extreme processes and applications of HIB nanofabrication have been addressed: How many extreme processes and applications of HIB technology have been developed in nanofabrication for integrated circuits, materials sciences, nano-optics, and bio-sciences applications? What are the main challenges in the extreme nanofabrication with HIB technology for high resolution and sensitivity applications?