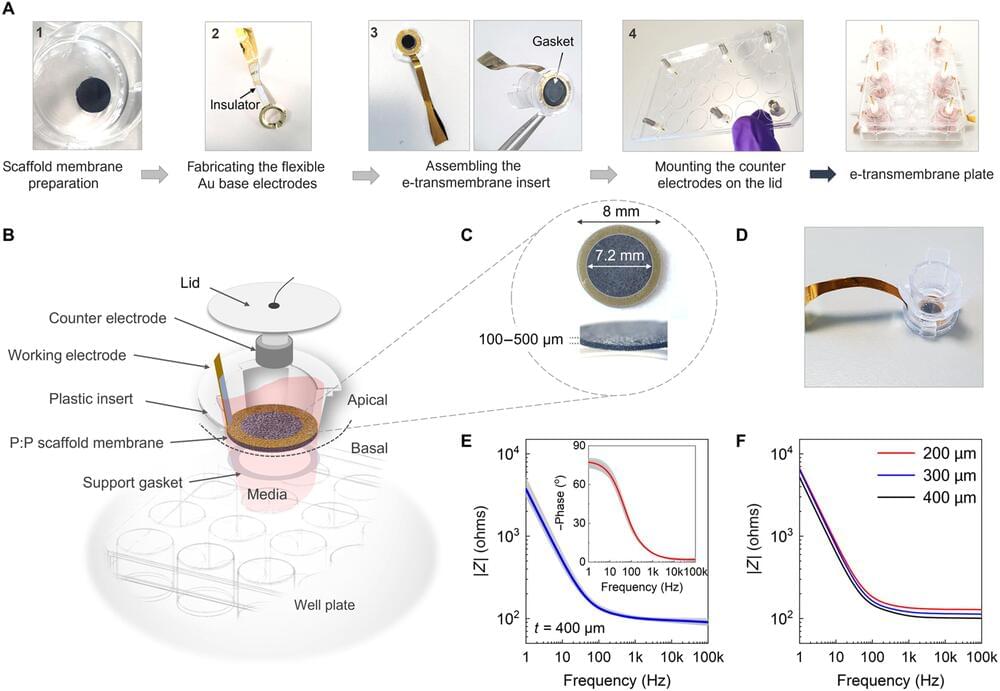

Researchers have used 3D cell culture models in the past decade to translate molecular targets during drug discovery processes to thereby transition from an existing predominantly 2D culture environment. In a new report now published in Science Advances, Charalampos Pitsalidis and a research team in physics and chemical engineering at the University of Science and Technology in Abu Dhabi, UAE and the University of Cambridge describe a multi-well plate bioelectronic platform named the e-transmembrane to support and monitor complex 3D cell architectures.

The team microengineered the scaffolds using poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene polystyrene sulfonate to function as separating membranes to isolate cell cultures and achieve real-time in situ recordings of cell growth and function. The high surface area to volume ratio allowed them to generate deep stratified tissues in a porous architecture. The platform is applicable as a universal resource for biologists to conduct next-generation high-throughput drug screening assays.