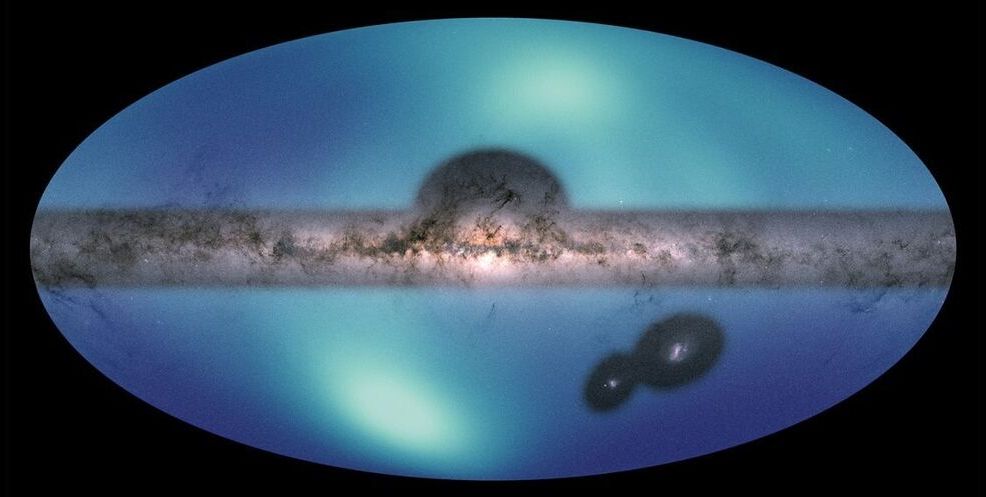

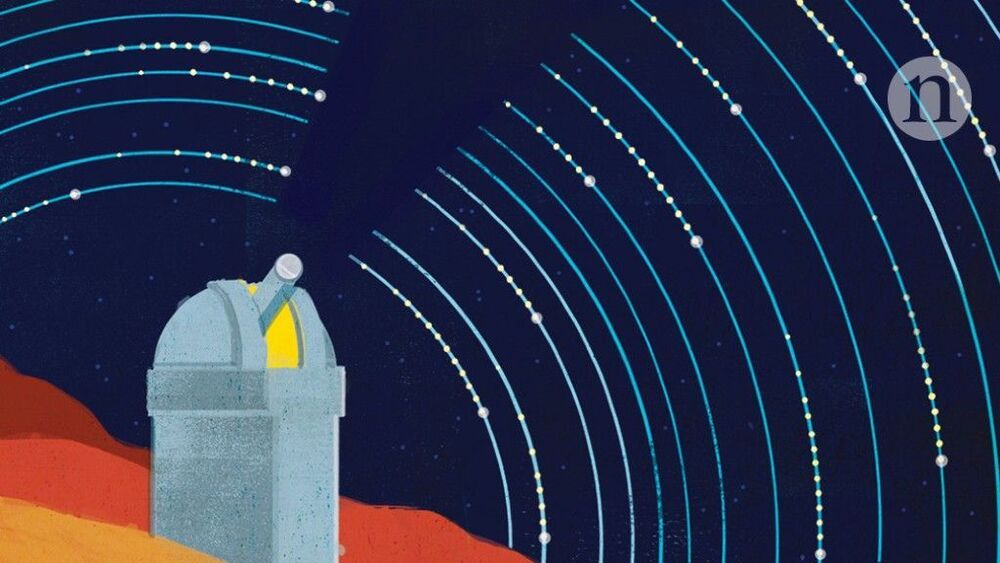

Astronomers are hoping to use the wake of stars to test the existing theories of dark matter.

Category: cosmology – Page 289

The detection of the axion would mark a key episode in the history of science. This hypothetical particle could resolve two fundamental problems of Modern Physics at the same time: the problem of Charge and Parity in the strong interaction, and the mystery of dark matter. However, in spite of the high scientific interest in finding it, the search at high radio frequency-above 6 GHz-has been almost left aside for the lack of the high sensitivity technology which could be built at reasonable cost. Until now.

The Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias (IAC) will participate in an international collaboration to develop the DALI (Dark-photons & Axion-Like particles Interferometer) experiment, an astro-particle telescope for dark matter whose scientific objective is the search for axions and paraphotons in the 6 to 60 GHz band. The prototype, proof of concept, is currently in the design and fabrication phase at the IAC. The white-paper describing the experiment has been accepted for publication in the Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics (JCAP).

Predicted by theory in the 1970’s, the axion is a hypothetical low mass particle that interacts weakly with standard particles such as nucleons and electrons, as well as with photons. These proposed interactions are studied to try to detect the axion with different types of instruments. One promising technique is to study the interaction of axions with standard photons.

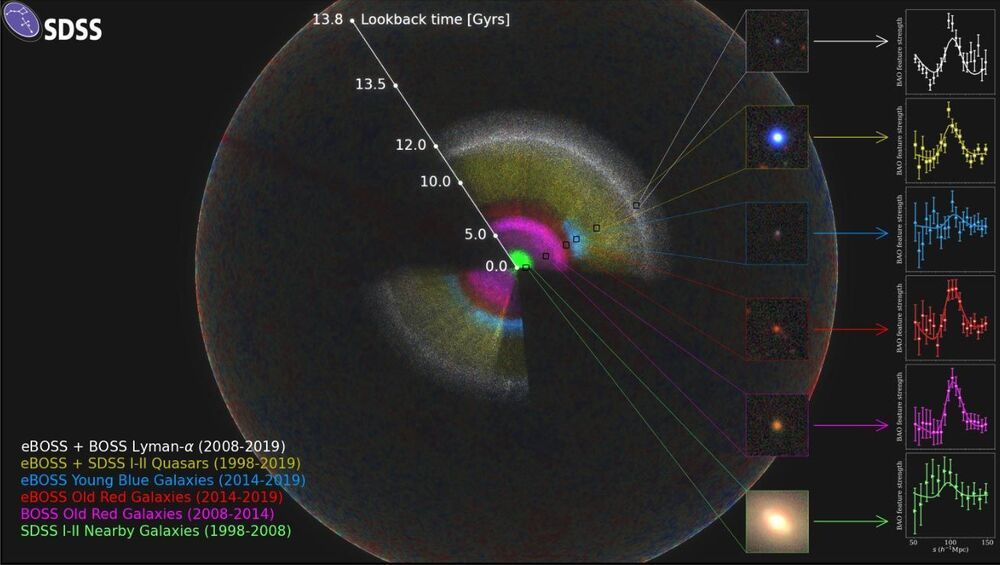

The extended Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey (eBOSS) collaboration has released its latest scientific results. These results include two studies on dark energy led by Prof. ZHAO Gongbo and Prof. WANG Yuting, respectively, from National Astronomical Observatories of the Chinese Academy of Sciences(NAOC).

The study led by Prof. Zhao was recently published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Based on eBOSS observations, Prof. ZHAO’s team measured the history of cosmic expansion and structure growth in a huge volume of the past universe, corresponding to a distance range between 0.7 and 1.8 billion light years away from us. This volume had never been probed before.

Some are blasted out of galaxies by interactions with black holes; others, which orbit supermassive black holes, can smash together in titanic explosions.

What Is Dark Matter?

Posted in cosmology

Circa 2018

An elusive substance that permeates the universe exerts many detectable gravitational influences yet eludes direct detection.

Circa 2018 o.o

In 2018 an international team of researchers using the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope and several other observatories uncovered, for the first time, a galaxy in our cosmic neighborhood that is missing most of its dark matter.

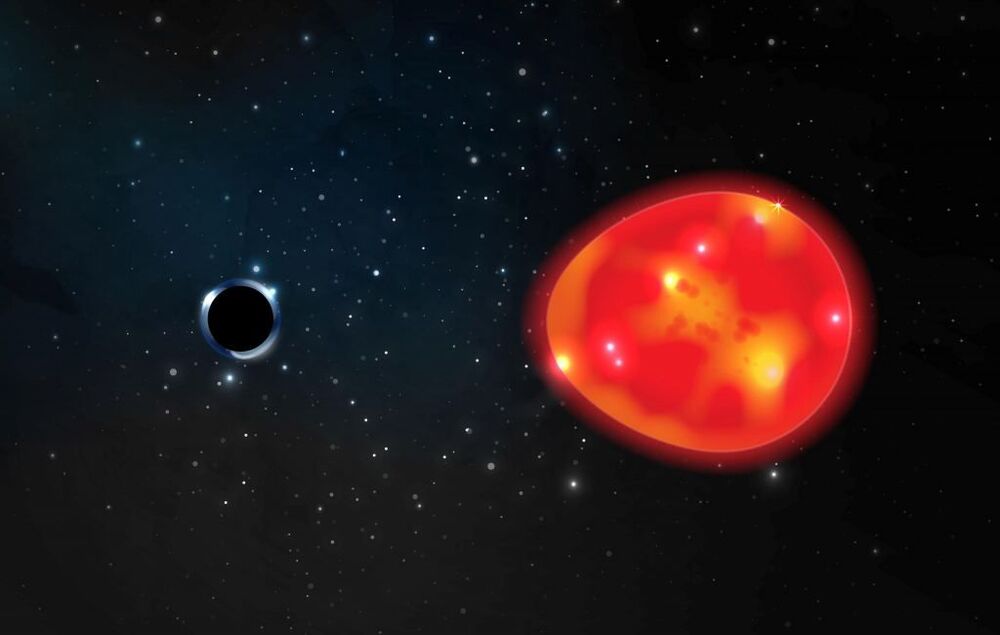

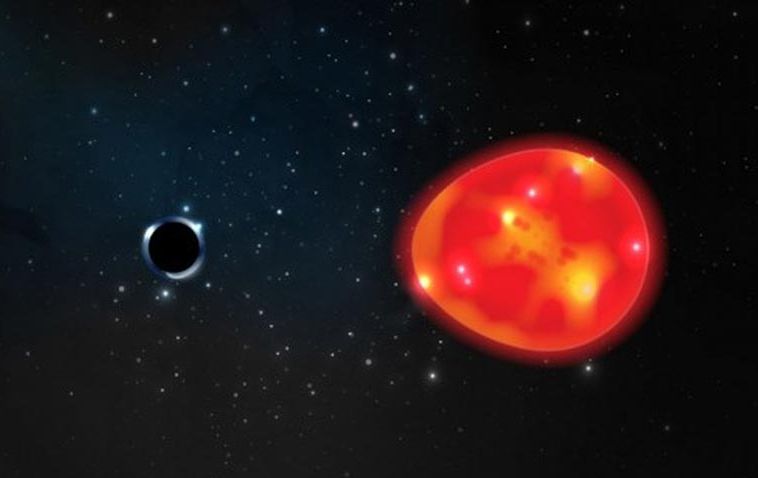

A red giant star may have a black hole companion that is only three solar masses in size.

In theory, a black hole is easy to make. Simply take a lump of matter, squeeze it into a sphere with a radius smaller than the Schwarzschild radius, and poof! You have a black hole. In practice, things aren’t so easy. When you squeeze matter, it pushes back, so it takes a star’s worth of weight to squeeze hard enough. Because of this, it’s generally thought that even the smallest black holes must be at least 5 solar masses in size. But a recent study shows the lower bound might be even smaller.

The work focuses red giant star known as V723 Monoceros. This star has a periodic wobble, meaning it’s locked in orbit with a companion object. The companion is too small and dark to see directly, so it must be either a neutron star or black hole. Upon closer inspection, it turns out the star is not just wobbling in orbit with its companion, it’s being gravitationally deformed by its companion, an effect known as tidal disruption.

Both the orbital wobble and the tidal disruption of V723 Mon can Doppler shift the light coming from it. Since both of these effects depend on the mass of the companion, you can calculate the companion mass. It turns out to be about 3 solar masses.

This shows also the hertz of reality circa 2016.

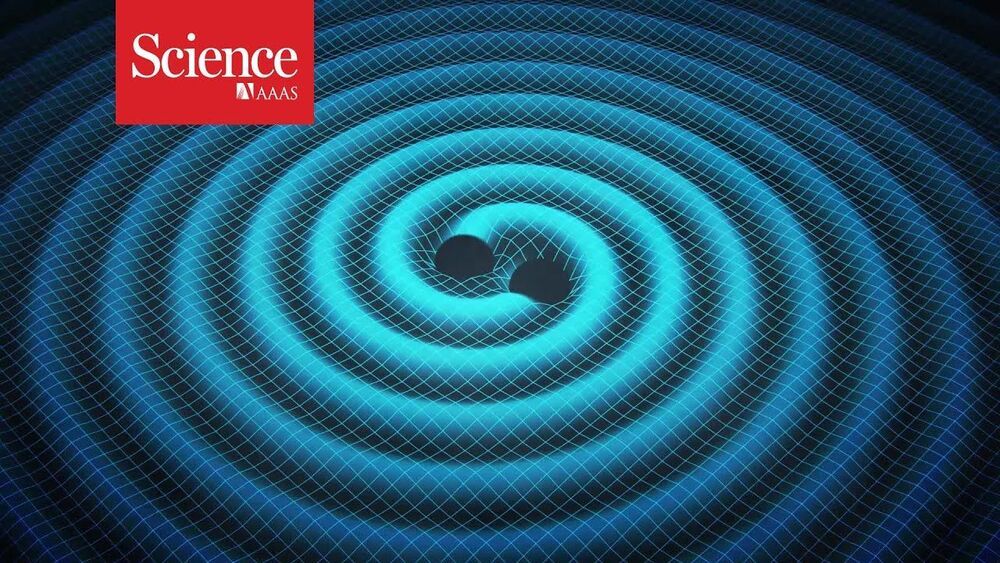

Long ago, deep in space, two massive black holes—the ultrastrong gravitational fields left behind by gigantic stars that collapsed to infinitesimal points—slowly drew together. The stellar ghosts spiraled ever closer, until, about 1.3 billion years ago, they whirled about each other at half the speed of light and finally merged. The collision sent a shudder through the universe: ripples in the fabric of space and time called gravitational waves. Five months ago, they washed past Earth. And, for the first time, physicists detected the waves, fulfilling a 4-decade quest and opening new eyes on the heavens.

Here’s the first person to spot those gravitational waves

The discovery marks a triumph for the 1000 physicists with the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO), a pair of gigantic instruments in Hanford, Washington, and Livingston, Louisiana. Rumors of the detection had circulated for months. Today, at a press conference in Washington, D.C., the LIGO team made it official. “We did it!” says David Reitze, a physicist and LIGO executive director at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena. “All the rumors swirling around out there got most of it right.”

On an incident response engagement, CISA found that cybercriminals exploited VPN flaws to acquire access and deploy Supernova malware on SolarWinds.

Scientists have discovered one of the smallest black holes on record – and the closest one to Earth found to date.

Researchers have dubbed it “The Unicorn,” in part because it is, so far, one of a kind, and in part because it was found in the constellation Monoceros – “The Unicorn.” The findings were published on April 21, 2021, in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

“When we looked at the data, this black hole – the Unicorn – just popped out,” said lead author Tharindu Jayasinghe, a doctoral student in astronomy at The Ohio State University and an Ohio State presidential fellow.