The researchers say that the monochrome painting — a dime’s width across — is a proof-of-concept that the extremely precise technique can be used to build nanoscale chip-based devices like computer circuits, conductive carbon nanotubes, and for extremely efficient targeted drug delivery.

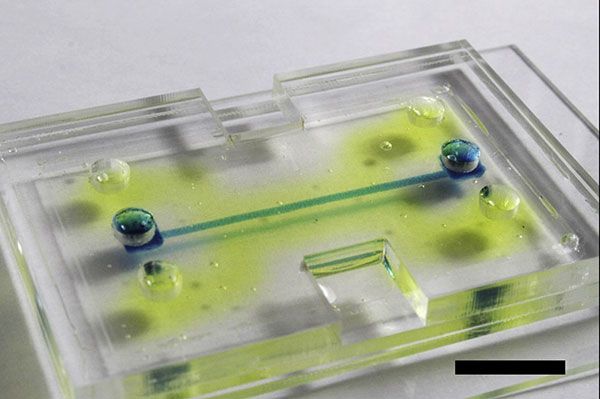

In order to reproduce the painting, the researchers used a technique first described by Rothemund and colleagues at IBM in 2009. The first step of the process involves folding DNA strands to create the desired shape, with short “staple strands” being used to literally staple the molecules. Then this pattern, which, at this stage, is floating in a saline solution, is poured into patches on a chip whose shapes match the DNA origami’s.

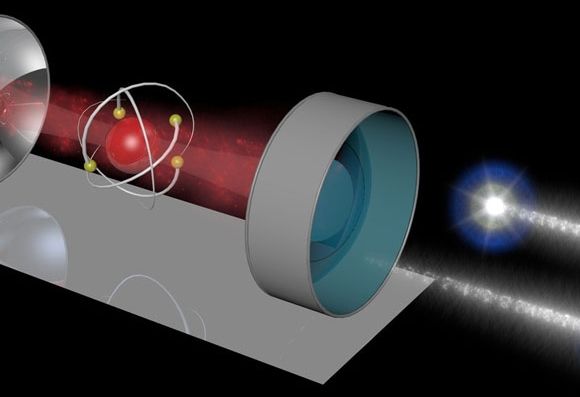

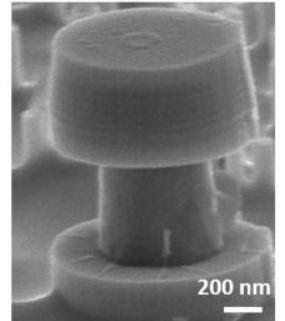

The folded DNA now acts as scaffolding onto which researchers then install fluorescent molecules inside microscopic light sources called photonic crystal cavities (PCC) — much like putting light bulbs into lamps.