It’s about my paper.

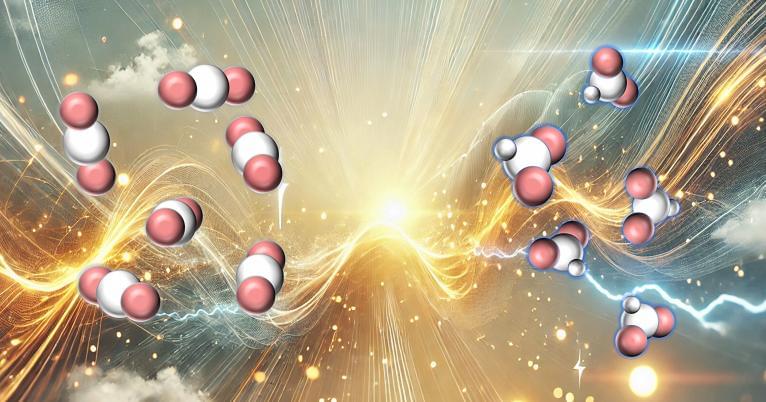

Dissolving polymers with organic solvents is the essential process in the research and development of polymeric materials, including polymer synthesis, refining, painting, and coating. Now more than ever recycling plastic waste is a particularly imperative part of reducing carbon produced by the materials development processes.

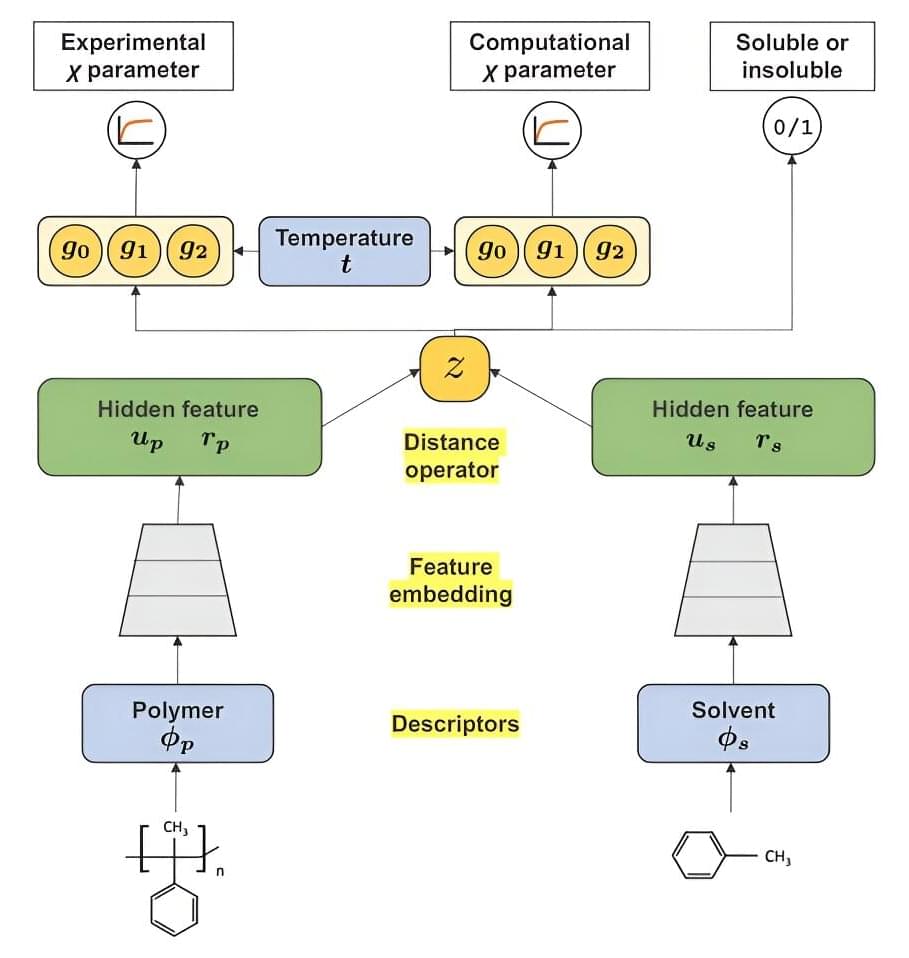

Polymers, in this instance, refer to plastics and plastic-like materials that require certain solvents to be able to effectively dissolve and therefore become recyclable, though it’s not as easy as it sounds. Utilizing Mitsubishi Chemical Group’s (MCG) databank of quantum chemistry calculations, scientists developed a novel machine learning system for determining the miscibility of any given polymer with its solvent candidates, referred to as χ (chi) parameters.

This system has enabled scientists to overcome the limitations arising from a limited amount of experimental data on the polymer-solvent miscibility by integrating massive data produced from the computer experiments using high-throughput quantum chemistry calculations.