Scientists at the Max Planck Institute have developed a synthetic pathway that can capture CO2 from the air more efficiently than in nature, and shown how to implement it into living bacteria. The technique could help make biofuels and other products in a sustainable way.

Plants are famous for their ability to convert carbon dioxide from the air into chemical energy to fuel their growth. With way too much CO2 in the atmosphere already and more being blasted out every day, it’s no wonder scientists are turning to this natural process to help rein levels back in, while producing fuels and other useful molecules on the side.

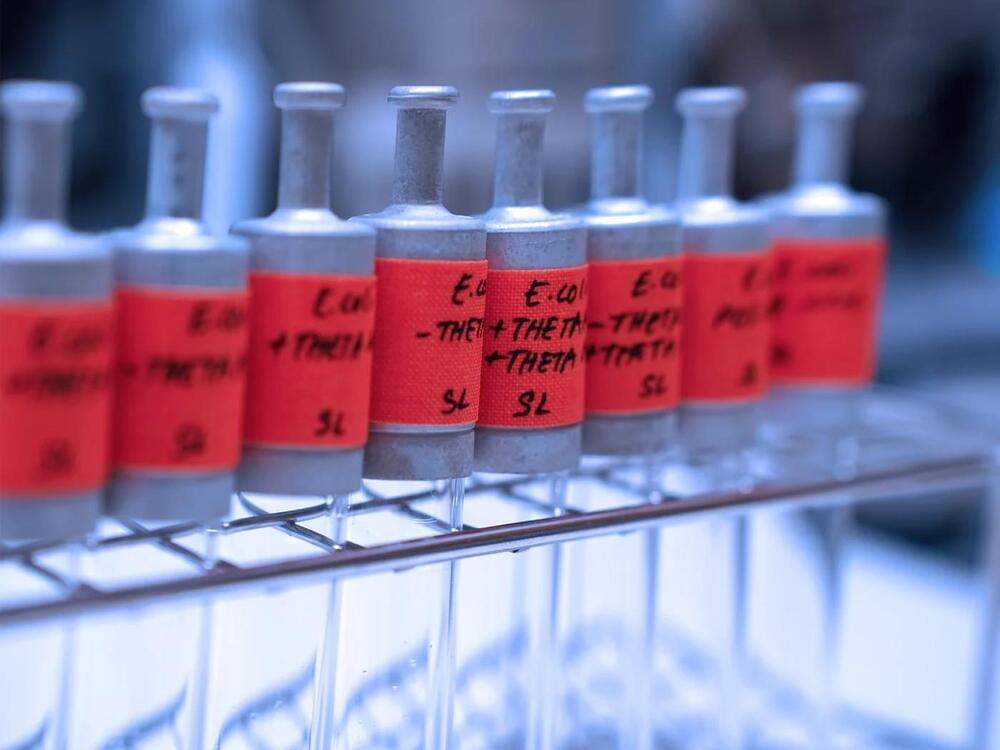

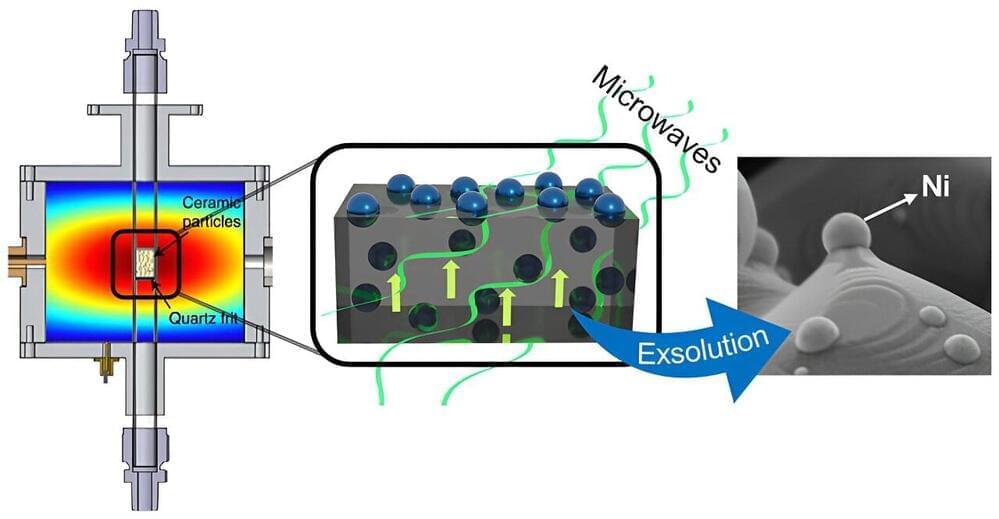

In the new study, Max Planck scientists developed a brand new CO2-fixation pathway that works even better than nature’s own tried-and-true method. They call it the THETA cycle, and it uses 17 different biocatalysts to produce a molecule called acetyl-CoA, which is a key building block in a range of biofuels, materials and pharmaceuticals.