Nov 12, 2023

How Einstein Unlocked the Quantum Universe and Created the Photon

Posted by Paul Battista in categories: energy, quantum physics

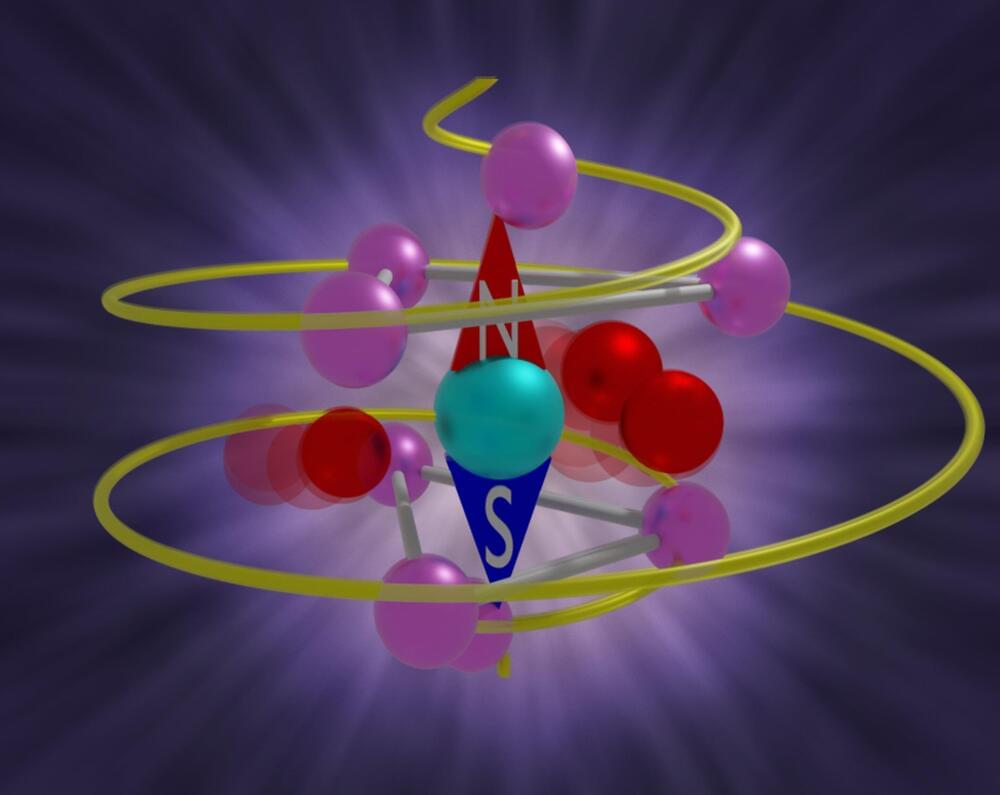

It started with a simple experiment that was all the rage in the early 20th century. And as is usually the case, simple experiments often go on to change the world, leading Einstein himself to open the revolutionary door to the quantum world.

Here’s the setup. You take a piece of metal. You shine a light on it. You wait for the electrons in the metal to get enough energy from the light that they pop off the surface and go flying out. You point some electron-detector at the metal to measure the number and energy of the electrons.

Continue reading “How Einstein Unlocked the Quantum Universe and Created the Photon” »