The first thing many media seem not to understand is the methodology followed by Space X, which is completely different from what the traditional aerospace builders do. While the latter prefer to spend their money on a long project life cycle, including long requirements discussion, and meticulous and detailed test engineering and integration phases, Space X opts for a methodology closer to the experimental scientific method: draw essential requirements, build a prototype, test, fail, learn from failures, build a new improved prototype, and try again. Each reiteration adds quality to the project, up to a point when the prototype is working well, and Falcon 9 (as a sample) becomes the space workhorse with any more competitors in the world. Is that so hard to be understood, for journalists?When a traditional project fails, many billions are wasted, and many years of work are canceled. When a “normal” failure occurs during Space X’s reiterative project development, very less resources are wasted. And, after all, during the expendable rockets’ age, all the rockets were always wasted, at every launch! The difference is incomparable. Another advantage of this method is its high flexibility. If a project lasts 10 years, it is difficult to take advantage of the technological advances: switching to new technology in a project initiated many years ago forces heavy requirements reviews and unavoidable delays. In a fail-and-repeat project, new technologies and new ideas can be adopted more easily and more quickly, as demonstrated by the thousands of changes and improvements applied to the different starships, super-heavy boosters, and raptor engine prototypes throughout history. Despite the misfortune bearers and the envious, the methodology works. The success of Space X in the launchers market doesn’t lie.

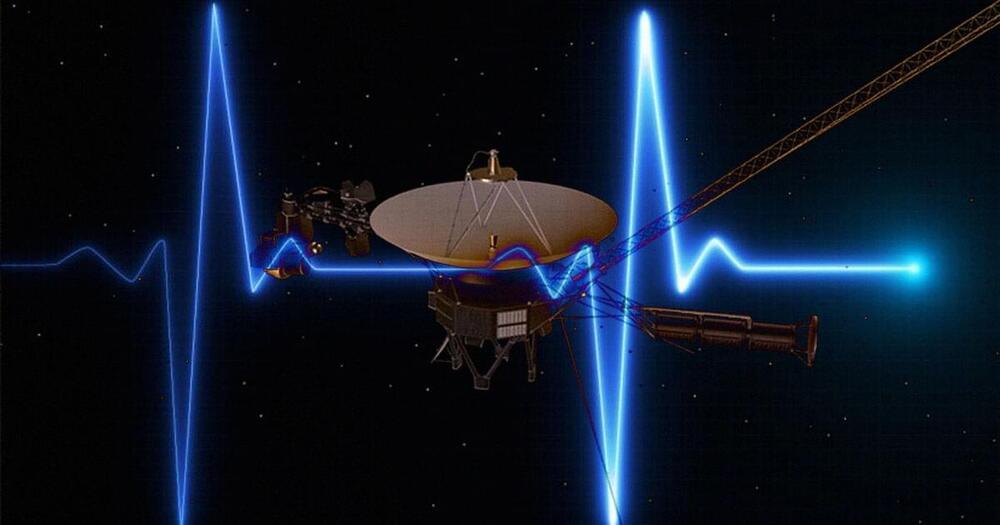

Starship 28 and the Super-Heavy Booster 10 made most of the expected work, and even more than what was expected: while the suborbital altitude was planned, the Starship spacecraft reached 230 km, a low Earth orbit altitude at more than 26,200 km/h. several tests were conducted after the engine cutoff, including a propellant transfer demo and payload dispenser test.

Only two operations have failed. The booster couldn’t make it to descend vertically on its engines, since only 3 of them reignited, and splashed in the Mexican Gulf at little more than 1,000 km/h. The Starship failed during the re-entry in the atmosphere, in the Indian Ocean. We could observe many insulating tiles flying away from the Starship’s body during the first part of the re-entry. At an altitude of 65 km, telemetry from Ship 28 was lost, and the vehicle was destroyed before splashing in the sea.