Nov 14, 2019

Ejected Star: How fast is fast?

Posted by Philip Raymond in categories: astronomy, science, space

Earlier today, Genevieve O’Hagan updated Lifeboat readers on this week’s momentous event in Astronomy. At least, I find it fascinating—and so, I wish to add perspective…

30 years ago, astronomer Jack Hills demonstrated the math behind what has become known as the “Hills Mechanism”. Until this week, the event that he described had never been observed.* But his peer astronomers agreed that the physics and math should make it possible…

Hills explained that under these conditions, a star might be accelerated to incredible speeds — and might be even flung out of its galaxy:

- Suppose that a binary star passes close to a black hole, like the one at the center of our galaxy

- The pair of self-orbiting stars is caught up in the gravity well of a black hole, but not sucked in

If conditions are right, one star ends up orbiting the back hole while the other is jettisoned at incredible speed, yet holding onto its mass and shape. All that energy comes from the gravity of the black hole and the former momentum of the captured star. [20 sec animation] [continue below]

This week, astronomers found clear evidence of this amazing event and traced it back to our galactic center: Five million years ago — as our ancestors learned to walk upright — a star that passed close to the massive black hole at The Milky Way center was flung away at a staggering 6 million Kmh. It is traveling so fast, that it is no longer bound to our galaxy or galactic cluster. It is headed out of the galaxy.

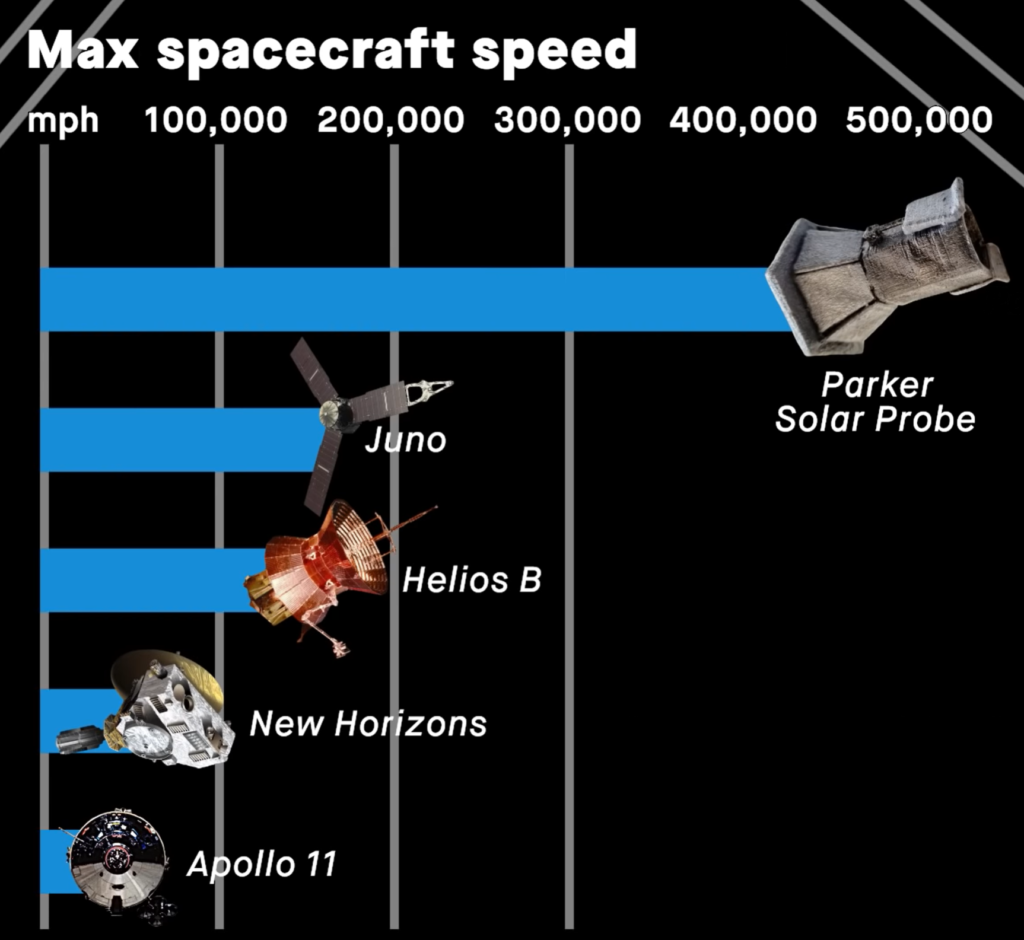

- Rifle Bullet: Can exceed Mach 3 (2,300 mph)

- Apollo Rocket: Reached 25,000 mph; Earth escape velocity.

- Juno Probe: 165,000 mph, a record prior to 2019. (It used Jupiter’s gravity to accelerate)

- Parker Probe: 213,000 mph (Nov 2019), but will soon reach 430,000 in a tight arc around the Sun