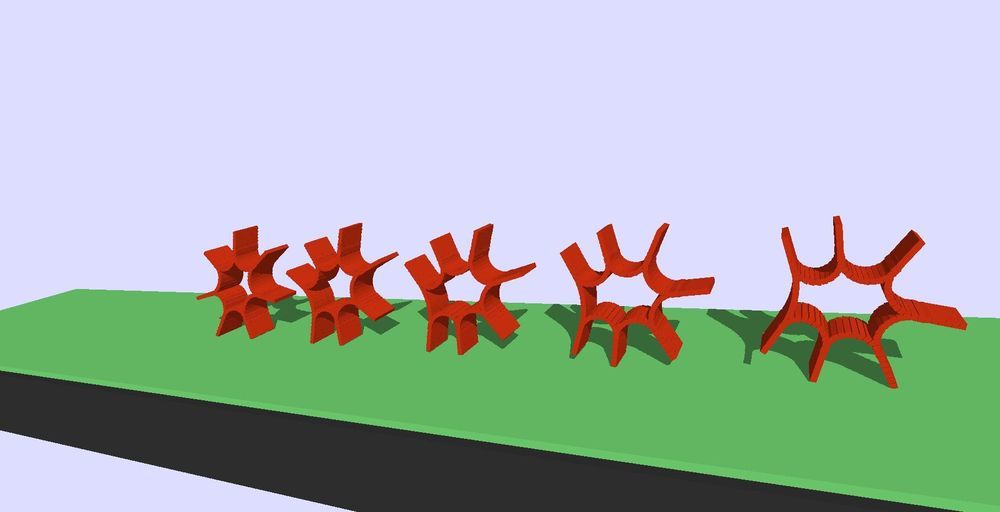

Scientists have recently explored the unique properties of nonlinear waves to facilitate a wide range of applications including impact mitigation, asymmetric transmission, switching and focusing. In a new study now published on Science Advances, Bolei Deng and a team of research scientists at Harvard, CNRS and the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering in the U.S. and France harnessed the propagation of nonlinear waves to make flexible structures crawl. They combined bioinspired experimental and theoretical methods to show how such pulse-driven locomotion could reach a maximum efficiency when the initiated pulses were solitons (solitary wave). The simple machine developed in the work could move across a wide range of surfaces and steer onward. The study expanded the variety of possible applications with nonlinear waves to offer a new platform for flexible machines.

Flexible structures that are capable of large deformation are attracting interest in bioengineering due to their intriguing static response and their ability to support elastic waves of large amplitude. By carefully controlling their geometry, the elastic energy landscape of highly deformable systems can be engineered to propagate a variety of nonlinear waves including vector solitons, transition waves and rarefaction pulses. The dynamic behavior of such structures demonstrate a very rich physics, while offering new opportunities to manipulate the propagation of mechanical signals. Such mechanisms can allow unidirectional propagation, wave guiding, mechanical logic and mitigation, among other applications.

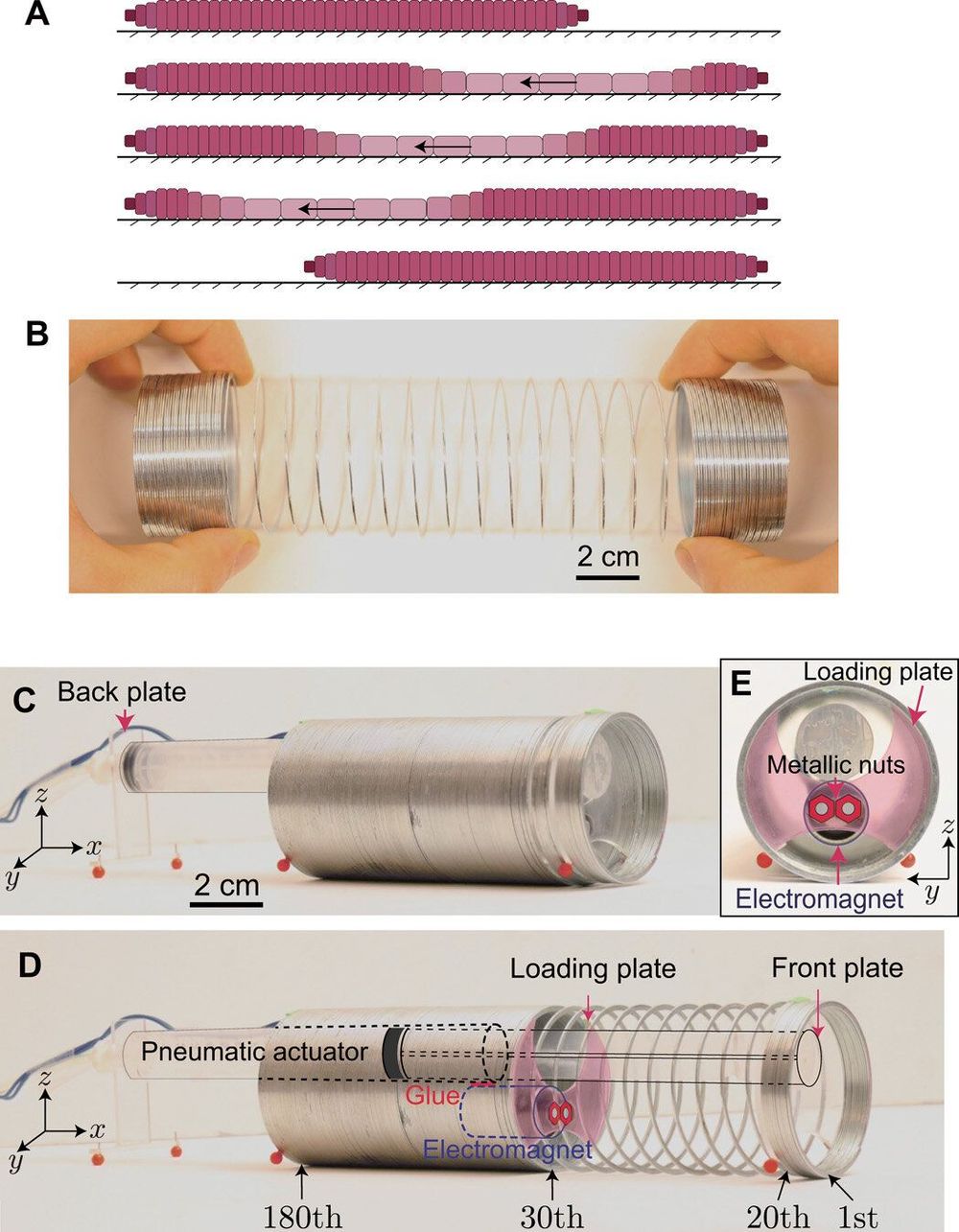

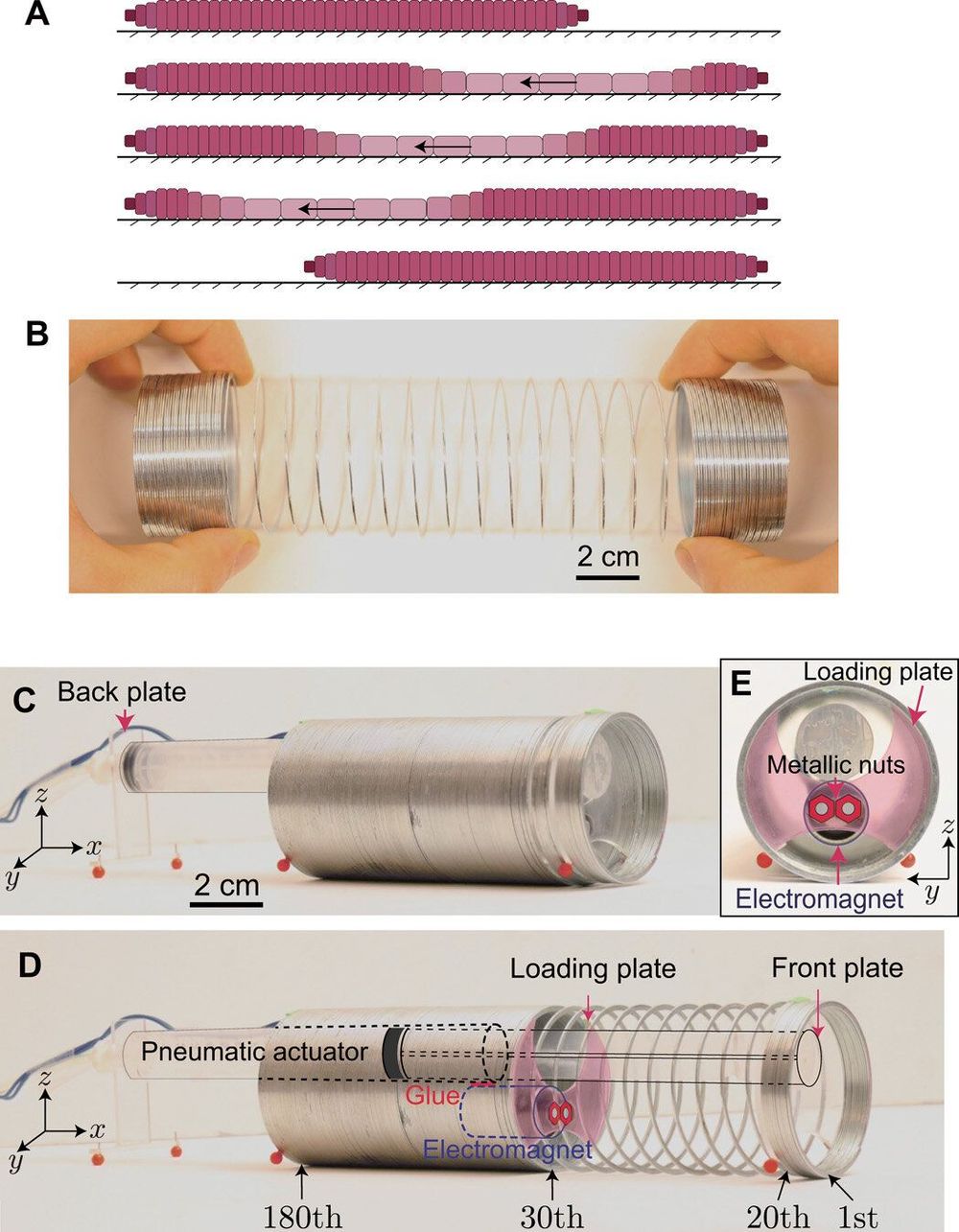

In this work, Deng et al. were inspired by the biological retrograde peristaltic wave motion in earthworms and the ability of linear elastic waves to generate motion in ultrasonic motors. The team showed the propagation of nonlinear elastic waves in flexible structures to provide opportunities for locomotion. As proof of concept, they focused on a Slinky – and used it to create a pulse-driven robot capable of propelling itself. They built the simple machine by connecting the Slinky to a pneumatic actuator. The team used an electromagnet and a plate embedded between the loops to initiate nonlinear pulses to propagate along the device from the front to the back, allowing the pulse directionality to dictate the simple robot to move forward. The results indicated the efficiency of such pulse-driven locomotion to be optimal with solitons – large amplitude nonlinear pulses with a constant velocity and stable shape along propagation.

[Image Source:

[Image Source: