Nov 28, 2024

Revealing Hidden Worlds: Monochromatic Light Unveils the Secrets of Crystalline Drops

Posted by Saúl Morales Rodriguéz in categories: materials, particle physics

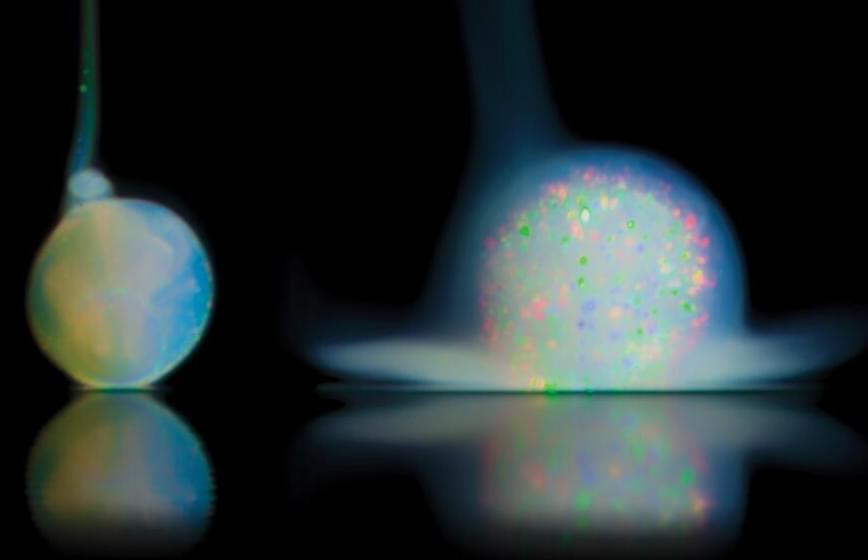

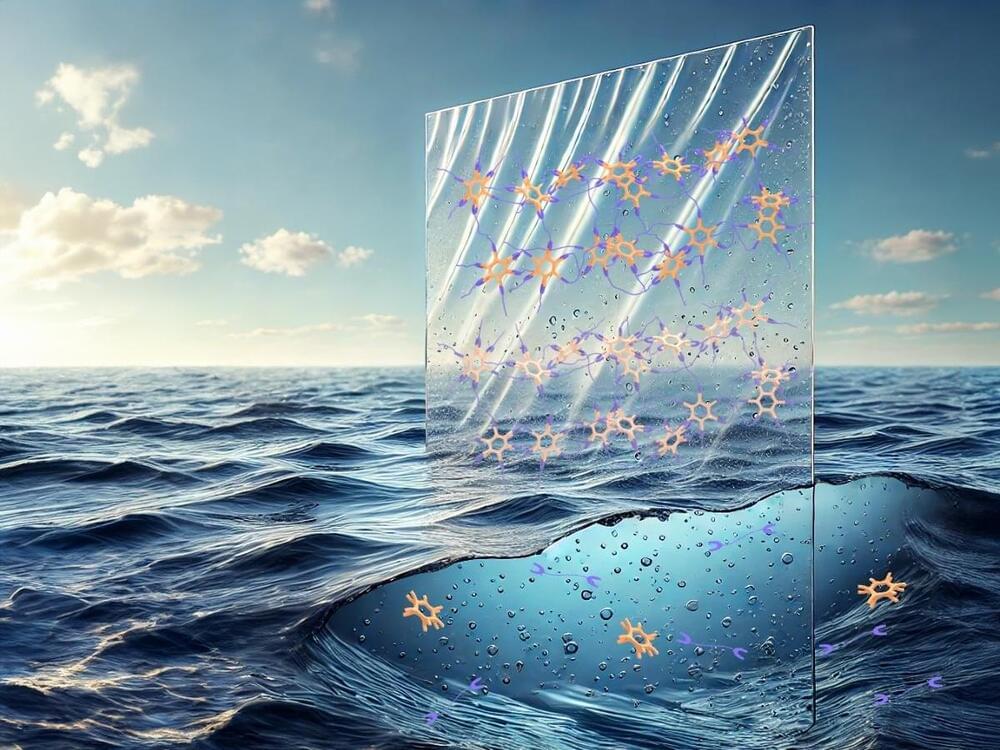

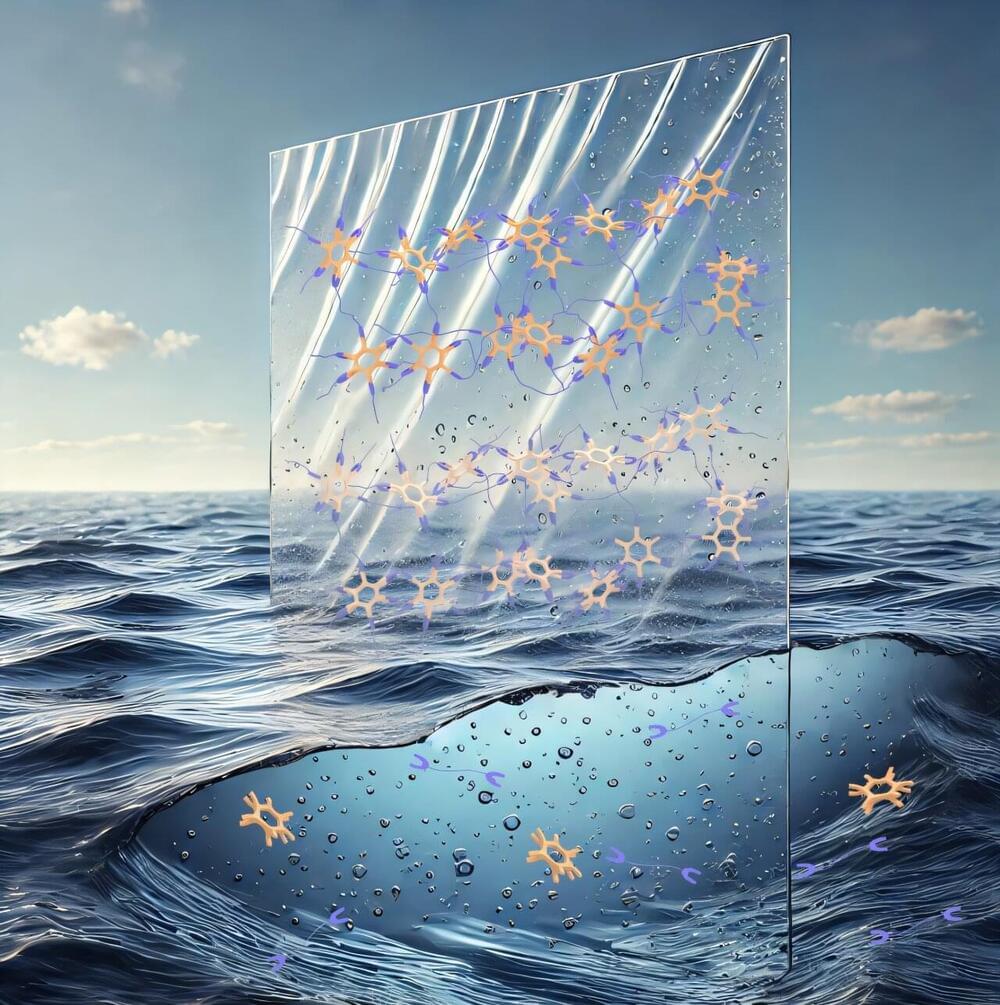

A new technique employing monochromatic light improves the study of internal structures in materials affected by light scattering, enabling detailed observation of particle concentrations.

When driving through a bank of fog, car headlights are only moderately helpful since the light is scattered by the water particles suspended in the air. A similar situation occurs when trying to observe the inside of a drop of milk in water or the internal structure of an opal gem with white light. In these cases, multiple light scattering effects prevent examination of the interior.