May 18, 2019

Scientists Discover a New Way Volcanoes Form, Sheds Light on Bermuda’s Origins

Posted by Genevieve Klien in category: materials

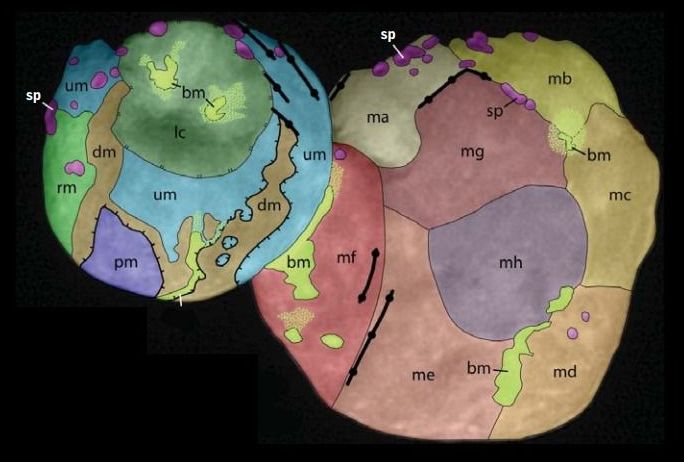

The ancient, now-dormant volcano on which the island of Bermuda sits formed in a completely unique way, scientists have discovered. The finding not only solves a long-standing mystery about the island’s volcanic origins, but it also describes a new way volcanoes form.

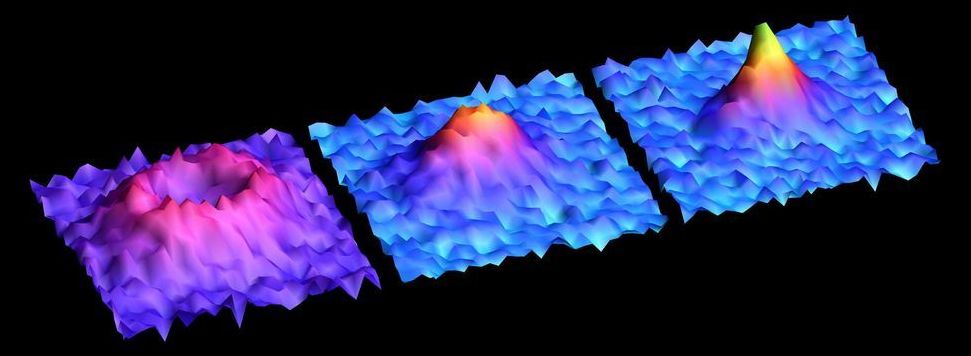

In studying a rock core sample taken from Bermuda, drilled from 1972, geoscientists have discovered the first direct evidence that material from deep within Earth’s mantle transition zone —a layer rich in water, crystals and melted rock — can percolate to the surface to form volcanoes.

Researchers have long known that volcanoes form when tectonic plates converge, or as a result of mantle plumes that rise from the core-mantle boundary to make hotspots at Earth’s crust.

Continue reading “Scientists Discover a New Way Volcanoes Form, Sheds Light on Bermuda’s Origins” »