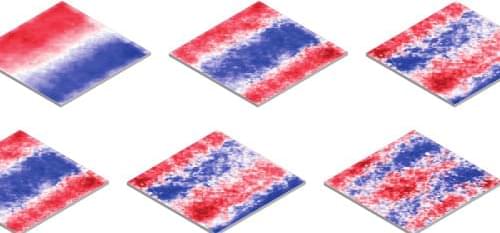

As part of its ongoing work to track variants, WHO’s Technical Advisory Group on SARS-CoV-2 Virus Evolution (TAG-VE) met on the 24 October 2022 to discuss the latest evidence on the Omicron variant of concern, and how its evolution is currently unfolding, in light of high levels of population immunity in many settings and country differences in the immune landscape. In particular, the public health implications of the rise of some Omicron variants, specifically XBB and its sublineages (indicated as XBB•, as well as BQ.1 and its sublineages (indicated as BQ.1•, were discussed. Based on currently available evidence, the TAG-VE does not feel that the overall phenotype of XBB* and BQ.1* diverge sufficiently from each other, or from other Omicron lineages with additional immune escape mutations, in terms of the necessary public health response, to warrant the designation of new variants of concern and assignment of a new label. The two sublineages remain part of Omicron, which continues to be a variant of concern. This decision will be reassessed regularly. If there is any significant development that warrant a change in public health strategy, WHO will promptly alert Member States and the public. XBB*XBB* is a recombinant of BA.2.10.1 and BA.2.75 sublineages. As of epidemiological week 40 (3 to 9 October), from the sequences submitted to GISAID, XBB* has a global prevalence of 1.3% and it has been detected in 35 countries. The TAG-VE discussed the available data on the growth advantage of this sublineage, and some early evidence on clinical severity and reinfection risk from Singapore and India, as well as inputs from other countries. There has been a broad increase in prevalence of XBB* in regional genomic surveillance, but it has not yet been consistently associated with an increase in new infections. While further studies are needed, the current data do not suggest there are substantial differences in disease severity for XBB* infections. There is, however, early evidence pointing at a higher reinfection risk, as compared to other circulating Omicron sublineages. Cases of reinfection were primarily limited to those with initial infection in the pre-Omicron period. As of now, there are no data to support escape from recent immune responses induced by other Omicron lineages. Whether the increased immune escape of XBB* is sufficient to drive new infection waves appears to depend on the regional immune landscape as affected by the size and timing of previous Omicron waves, as well as the COVID-19 vaccination coverage. BQ.1*BQ.1* is a sublineage of BA.5, which carries spike mutations in some key antigenic sites, including K444T and N460K. In addition to these mutations, the sublineage BQ.1.1 carries an additional spike mutation in a key antigenic site (i.e. R346T). As of epidemiological week 40 (3 to 9 October), from the sequences submitted to GISAID, BQ.1* has a prevalence of 6% and it has been detected in 65 countries. While there are no data on severity or immune escape from studies in humans, BQ.1* is showing a significant growth advantage over other circulating Omicron sublineages in many settings, including Europe and the US, and therefore warrants close monitoring. It is likely that these additional mutations have conferred an immune escape advantage over other circulating Omicron sublineages, and therefore a higher reinfection risk is a possibility that needs further investigation. At this time there is no epidemiologic data to suggest an increase in disease severity. The impact of the observed immunological changes on vaccine escape remains to be established. Based on currently available knowledge, protection by vaccines (both the index and the recently introduced bivalent vaccines) against infection may be reduced but no major impact on protection against severe disease is foreseen. Overall summaryThe Omicron variant of concern remains the dominant variant circulating globally, accounting for nearly all sequences reported to GISAID[1]. While we are looking at a vast genetic diversity of Omicron sublineages, they currently display similar clinical outcomes, but with differences in immune escape potential. The potential impact of these variants is strongly influenced by the regional immune landscape. While reinfections have become an increasingly higher proportion of all infections, this is primarily seen in the background of non-Omicron primary infections. With waning immune response from initial waves of Omicron infection, and further evolution of Omicron variants, it is likely that reinfections may rise further. The role of the TAG-VE is to alert WHO if a variant with a substantially different phenotype (e.g. a variant that can cause a more severe disease or lead to large epidemic waves causing increased burden to the healthcare system) is emerging and likely to pose a significant threat. Based on currently available evidence, the TAG-VE does not feel that the overall phenotype of XBB* and BQ.1* diverge sufficiently from each other, or from other Omicron sublineages with additional immune escape mutations, in terms of the necessary public health response, to warrant the designation of a new variant of concern and assignment of a new label, but the situation will be reassessed regularly. We note these two sublineages remain part of Omicron, which is a variant of concern with very high reinfection and vaccination breakthrough potential, and surges in new infections should be handled accordingly. While so far there is no epidemiological evidence that these sublineages will be of substantially greater risk compared to other Omicron sublineages, we note that this assessment is based on data from sentinel nations and may not be fully generalizable to other settings. Wide-ranging, systematic laboratory-based efforts are urgently needed to make such determinations rapidly and with global interpretability. WHO will continue to closely monitor the XBB* and BQ.1* lineages as part of Omicron and requests countries to continue to be vigilant, to monitor and report sequences, as well as to conduct independent and comparative analyses of the different Omicron sublineages. The TAG-VE meets regularly and continues to assess the available data on the transmissibility, clinical severity, and immune escape potential of variants, including the potential impact on diagnostics, therapeutics, and the effectiveness of vaccines in preventing infection and/or severe disease. [1] Weekly epidemiological update on COVID-19 — 26 October 2022 (who.int)